Blog

“All Eggs Under the Great! Alexander and the Epithet Megas” Shane Wallace

On the evening of the 15th June 2022, CANI was proud to host Dr Shane Wallace from Trinity College Dublin in the final lecture of the 21/22 academic calendar. Having mused over the CANI bookstore and been refreshed with summer drinks, the CANI audience settled down with their handout of primary sources to listen to Dr Wallace’s lecture: ‘All Eggs Under the Great! Alexander and the Epithet Megas’.

To ease the audience into the topic, Dr Wallace employed the wit of Irish writer Jonathan Swift (1667-1745) who in his satire A Discourse, To Prove the Antiquity of the English Tongue joked about the origins of the Alexanders epithet: “Alexander the Great was very fond of eggs roasted in hot ashes. As soon as his cooks heard him come home to dinner or supper, they called aloud to their under-officers, All eggs under the Grate: which repeated every day at noon and evening, made strangers think it was that prince’s real name…” (Swift, 287).

Dr Wallace proceeded to show us that “Great” is a common epithet throughout history e.g., Frederick the Great, Muhammad Ali (the greatest) and even the Great Gonzo from the Muppets! Therefore, Alexander is certainly not alone in the realms of “greatness” and when placed alongside these other more recent historical figures he arguably is not even the most famous. Nor is he the earliest historical person with the epithet “the Great” because some Persian kings such as Cyrus the Great and Darius the Great predate him by at least two centuries. However, Dr Wallace continues, by the era of Roman dominance – Alexander is undoubtably the most famous of those known as “the Great”.

This brought the lecture on to contested historiographical question: How early was Alexander called “the Great”? There is an absence of evidence to verify if Alexander held the epithet “Megas” during his lifetime or even immediately after it. In fact, the earliest writer to call Alexander “Great” comes from the Roman playwright Plautus c.193 BC in his Mostellaria (3.2.775), some 130 years after Alexander’s death. After this there is another gap in the evidence until Cicero refers to Alexander as “the Great” c. 62 BC around which time we have a Roman general appropriating the epithet “the Great” himself – Pompeius Magnus: Pompey the Great.

Although the references to Alexander as “the great” were relatively scant – there were numerous historical figures who were called “the great” (by themselves or others) in the immediate centuries after Alexander’s death. Demetrius the Great (also given the epithet “the Besieger”) was given his epithet by his Athenian soldiers who commissioned a bronze monument to him in the Athenian agora after his death. But also, the major Hellenistic kings too such as Antiochus the Great who gave himself the title after victories in Mesopotamia and also Ptolemy III who took the epithet “Great King” when he too took lands in the east. It is possible that these two successor kings would take on the epithet “Great” whenever they completed conquests of lands that Alexander had conquered during his campaigns. This connection of the epithet “the Great” and Alexander’s conquests can also be found with the Roman generals Pompey and Scipio Africanus.

Dr Wallace highlighted the point that before Alexander’s untimely death he had planned to campaign around the Arabian Peninsula and then onwards west likely into Africa. It is therefore a possibility that these two Roman generals, like the Hellenistic kings in the east, took on their epithets when they won important victories in Africa – a land that although was in Alexander’s plans nonetheless escaped the Macedonian king. Indeed, is it possible that even Julius Caesar might also have taken the epithet “the Great” had he been successful in his Parthian campaigns in the east which he was due to depart for only days after he was assassinated. Dr Wallace therefore concluded that although Alexander was not explicitly named “the Great” in the contemporary sources his influence is still detectable in his Hellenistic successors and Roman generals who all assumed the epithet after emulating Alexander’s conquests.

The Classical Association in Northern Ireland would like to sincerely thank Dr Shane Wallace for his insightful lecture and for concluding our 21/22 programme. Furthermore, we would like to extend our appreciation to our members for their continued support and throughout the year.

Barry Trainor

Why Do We Need New Translations of Ancient Texts? Ines Choi

John Dryden remarks in the preface to Ovid’s Epistles that the art of translation can be classified into three types: metaphrasing, paraphrasing and imitating (Dryden (1776, preface). The first constitutes the “word-by-word, line-by-line” approach which he deems ill-fitting (Dryden (1776) preface). This literal approach focuses on the “mechanics” of language and calls into question the “practicality” of embarking on re-translations. Its limitations are evident when using Google Translate on ancient texts which are heavy with meaning and nuance. Additionally, it lacks a deeper sensitivity to context, perspective and values which are reflected in language and form over time. New translations are incredibly important and arguably essential to unearth fresh perspectives, address cultural misconceptions in past translations, understand the impact of domesticating and/or foreignising a translation (“Foreignisation” and “domestication” are terms coined by translation theorist Lawrence Venuti in his 1995 book The Translator’s Invisibility), and lastly to reinvigorate a text in a creative way, promoting inclusion and appeal to a broader community.

New translations of ancient texts provide original, raw, sometimes broader and more complex perspectives through which to see a narrative. Emily Wilson’s translation of Homer’s Odyssey is a clear example of this approach. In a recent lecture, Wilson articulates the need for an authentic and new vision for the Odyssey using multiple perspectives because she felt previous translations were too limiting (Wilson (2019b)). The first lines of the poem strongly reveal her intentions:

Tell me about a complicated man…how he worked to save his life and bring his men back home. He failed to keep them safe; poor fools…the god kept them from home. Now…tell the old story for our modern times. (Wilson (2018), 1)

Her rendering of the Greek “ανδρα μοι έννεπε, Μουσα, πολυτροπον…” (Homer, Odyssey line 1 (Murray)) is striking because “πολυτροπον” (literally meaning “many-turned”) describing “ανδρα” (Odysseus) is translated here for the first time as “complicated.” Past translations have opted for “many twists and turns” to refer to the complexities of Odysseus’ geographical journey at the hands of the gods, such as George Musgrave’s “tost to and fro by fate”: a passive interpretation (Tracey (2018)). Others like Fagles and Rieu have considered the “many twists and turns” to convey Odysseus’ character, in the sense that he is ‘manipulating’ the lives of others with the “twists and turns” of his character (Roberts (2020)). This is emphasized in the proceeding lines by how he had a responsibility to protect his men yet “failed to keep them safe”, reducing them to “poor fools” subject to divine will – an internalized portrayal of Odysseus. Wilson’s version of “complicated” encapsulates both of these points of view. While she remains faithful to the vague nature surrounding the word “πολυτροπον”, she prioritizes authenticity to present the “vast complexities of Odysseus in his many disguises” (Wilson (2019a)), and provide greater insight into his multi-faceted character and the elaborate story ahead.

Although the title of the poem suggests Odysseus should be the main focus, Wilson also highlights other characters because they contribute to the narrative, particularly the conflict within his character. While other translations silence their viewpoints, Wilson sympathizes for those he abandons, mutilates, and allows to die (his family, his men, Calypso, Circe, Nausicaa) as he sacrifices their nostos (homecoming) – a central theme of the epic – in order to achieve his own. In this way, she immediately undermines the image of Odysseus as an “unproblematic male western hero” or a “good guy” and instead invites the reader to engage more critically with his “moral ambiguity” (Tracey (2018)).

According to Wilson, while “lots of translators only present the narrative in one view,” (Wilson (2019b)) she considers numerous possibilities. She narrows in on the emotions and broader themes, delivering her translation with a particular sensitivity and rawness. Another instance is found in Book 22’s gruesome depiction of the hanging of the slave-women who “slept with” (more likely raped) the suitors. What distinguishes Wilson’s translation in this excerpt is the dignity she injects and sympathy she has for the women. In the Greek, as the women are on the verge of death, they are compared to trapped birds. This expression is rendered in different ways. Richard Fagles likens their situation to “flying in for a cozy nest but a grizzly bed receives them,” (Homer, Odyssey (Fagles, p.378)) where the animalistic lexicon dehumanizes and degrades the women by trivializing their fates.

However, Wilson’s interpretation is arguably more convincing and insightful – the women are like the birds with their “own motivations and perspectives.” (Wilson (2019b)) It is no coincidence that the theme of homecoming recurs, as they fly back to the αυλις (can be a human dwelling), and like Odysseus, they want a nostos. Wilson’s translation “…as doves or thrushes spread their wings to fly home” (Homer, Odyssey (Wilson (2018) 409) reinforces the importance of nostos to demonstrate their desperate plight, thereby evoking pathos for the women who will never have one.

Her intentions and priorities are echoed by translator Josee Kamoun: “It is through the desire to open up new perspectives on the original work and to multiply its ramifications that a retranslation is justified” (Kamoun (2018)). We see how distinct word choices seem immaterial on a microscopic level but hugely impact the overall picture – for instance, the concept of a “good guy/hero” in the Classical World is scrutinized and the perception of who and what is important in the text is broadened. These additional reflections created by the modern translation of a timeless text provide a fresh literary perspective on elements of the poem that have previously been neglected.

New translations of ancient texts furthermore address entrenched misconceptions within literature regarding disenfranchised groups in that society – undeniably applicable to society today. This forces readers to contemplate contemporary ethical questions. Again in the Odyssey, many translators treat the word “slave” in a taboo manner. It could stem from biases surrounding their race, gender or socio-economic status or an aim to glamorise this world, where Odysseus, the quintessential “good-guy”, is not supposed to own slaves. Yet he does, touching on an ‘uncomfortable truth’. While Fagles and Rieu refer to Eurymedusa, a slave of Nausicaa, utilising euphemistic language such as “chambermaiden” and “nurse” and male slaves as “servant” and “swineherd”, Wilson uses “slave” (Roberts (2020)) to honestly portray the world that the literature is set in, where slaves were not free and had no voice. By diverging from past translations, Wilson illuminates the horror of slavery, a “condition of existence” (Rieu (2003) xxvi) and its integration into the hierarchical framework of society. Unfortunately, this resonates with the modern conscience, with the Guardian reporting in 2019 that there are still over 40 million slaves globally (Hodal (2019)).

Unsurprising given the misogyny prevalent in the Classical world, a large number of women were victims of slavery. Unfortunately, some translators insert gendered abuse and incrimination into certain passages, unparalleled in the source language. Returning to the slave-women in Book 22, this scene has previously been depicted using misogynistic slurs:

Fagles p.378: “You sluts – the suitors’ whores!”

Fitzgerald p.569: “I would not give the clean death of a beast to trolls…you sluts”

Lombardo p.548: “the suitor’s sluts”

The source text describes the women as “αι…παρα τε μνηστηριον ιαυον…” (Homer, Odyssey (Murray, lines 464-465), translating literally as “the women…lying besides the suitors”. Despite arguments that it reflects sexist attitudes in the Homeric era, there is nothing in the Greek to suggest they should be portrayed in a derogatory manner. Wilson, making visible the “cracks and fissures in the [poem’s] constructed fantasy” (Wilson (2018)), describes the women more neutrally as “the girls…who laid beside the suitors” (Wilson (2018) 409). She corrects the mistakenly embedded misogyny in previous translations and exposes the culture at that time of women, even as minors, being sexually exploited – again, a frightening reality existing today. She challenges the misguided assumption that women should be viewed and treated as sexual objects, stressing that they too are human. This can be seen in the violent description of their deaths touching on the movement of their feet, which Wilson describes as “twitching for a little while”, pitying the women and (Wilson (2018) 409) emphasizing their vulnerability in the face of the suitors they were forced to sleep with. This contrasts to:

Fagles, p.379: “They kicked up heels”

Fitzgerald p.569: “Their feet danced for a little”

Lombardo p.549: “Their feet fluttered”

These translations dehumanise the women. The first two condemn their sexual behaviour, as they are “dancing” like party-girls driven by desire. The third, through the verb “fluttered”, treats the women as animals. All three strongly justify their fates on account of their sexual behaviour. Again, these pejorative terms have been inserted into the Greek and are more reflective of contemporary sexist attitudes. Re-translating ancient texts compel the readers to reconsider past assumptions embedded in translations and wider implications they hold about society’s standards.

Cicero, writing in the 1st century BC, defines translation as “putting it into a language which conforms to our ways” (Hardwick and Taplin (2010)) In some cases, this is necessary to avoid punishment. For example, the lyric poetry of Sappho, a lesbian poet writing in the 6th century BC, have been translated into Russian. However, under the Soviet regime where homosexuality had harsh consequences, her works were adapted to appear strictly heterosexual through de-eroticising, gender-switching or simply omitting signs of homosexuality (Barker (2020)). On the other hand, translators strive to “foreignize” translations to acknowledge differences between the source and target cultures. For instance, Tony Harrison’s translation of Aeschylus’ Oresteia uses the words such as “he-child” and “she-child” (instead of “son” and “daughter”) and “bed-bond” and “blood-bond” (“marriage” and “blood-relationship”) to express that the play is not about his culture (Harrison (1981). However, the acts of “foreignising” and “domesticating” do not have to be mutually exclusive.

Wilson includes some details considered to be “foreignising”, like the goddess Demeter having cornrows in her hair (Gabrielson (2018) 115). This challenges the societal assumption that all gods/goddesses are white. At the same time, she remains faithful to the oral tradition of Homer by setting her translation in iambic pentameter, the closest equivalent in the Anglophone tradition to dactylic hexameter, the original metre of the Odyssey. Hence, retranslating these ancient texts are meaningful as they allow translators to explore, understand and identify the impact of ‘foreignising’ and domesticating characters and subjects, and how they reflect cultural norms.

In a slightly different vein, new translations of ancient texts have the power to revitalize texts in innovative ways. Oliver Taplin from Oxford University points out that translation is often considered an art that is exclusively literary (Hardwick and Taplin (2010)). However, he suggests that translation can assume a variety of forms and contexts. This is supported by Margherita Laera who deconstructs what it means “to translate.” She argues that translation is something that is always changing, subject to culture and society, so it can therefore be coined as an adaptation (Laera (2019) 25-26). Translations as “adaptations” are capable of facilitating conversation on important social issues. This is demonstrated by Euripides’ tragedy Medea, which has been “translated” into multiple forms/contexts since it was first performed in 431 BC. In Guy Butler’s South African version of Medea performed in 1990, Medea and Jason are in a mixed-race marriage and the race of the children is unclear, raising deeper questions about whether colour matters (Griffiths (2006) 112), especially relevant under Apartheid. In contrast to this political and racial commentary, Brendan Kennelly’s “translation” is centred around his personal experience in a psychiatric institution and how he contextualizes Medea in a similar situation, driven to the point of anger and insanity by an abusive relationship (Griffiths (2006) 113). The impact of retranslating ancient texts in new contexts and forms is significant and in both cases here allow the audience to engage with contemporary emotional, political and social issues in a more creative and impactful way.

Finally, new translations can be agents of inclusion, making texts accessible to all. Composer Julian Anderson, through his 2014 operatic version of Sophocles’ Theban plays, expresses the characters and underlying themes through music. For example, in Antigone, Anderson represents Creon’s drive for power by notating the orchestral score with individual beats and the Chorus repeatedly singing “Your Word Is Law”. In a 2018 interview, he reveals how on the page, this scene looked like “bars of a prison” (Nicholls (2018) 26-27), intended to create an atmosphere of oppression and bring out the dictatorial side of his character. By staging the Thebans in this way, this “translation” of form would appeal to those who learn through visual stimuli and engage with texts through analysing the music, as opposed to reading, the most popular medium through which to access ancient texts. Similarly, retranslating attracts a larger audience who engage with these timeless texts in different ways.

The need for new translations of ancient texts is clear and arguably its importance is increasing. New translations provide a fresh lens with which to examine a work, discover new elements and explore more comprehensive perspectives. At the same they can eradicate bias in past renderings, and invite readers to consider the impact of domesticating and foreignizing a text to either reflect or reject the values of a text within the context of a specific culture. Finally, retranslations explore deeper contemporary political and social issues and include the broader population in these dialogues. Ultimately, Classical texts more often than not deal with the human condition, from the most noble acts to the most depraved, which is relevant across cultures and time.

Ines Choi

Bibliography

Barker, G. ‘Classics and Queerness: Translating Sappho straight into Russian’, University College of London (2020) [lecture]

Dryden, J. Ovid’s Epistles: With His Armours. London (1776)

Fagles, R. Homer’s The Odyssey. London (2006)

Fitzgerald, R. Homer’s The Odyssey. New York (1961)

Gabrielson, M. ‘Homer, Emily Wilson, trans. The Odyssey’, New England Classical Journal (2018)

Griffiths, E. Medea. London and New York (2006)

Harrison, T. The Oresteia: A trilogy by Aeschylus. London (1981)

Murray, A.T. Homer, The Odyssey. London (1919)

Kamoun, J. Orwell’s 1984. Paris (2018)

Laera, M. Theatre & Translation. London (2019)

Lombardo, S. Homer’s The Odyssey. Cambridge (2000)

Hardwick, L. and Taplin, O. ‘What is Translation?’, University of Oxford Podcasts (2010)

Nicholls, M. ‘Staging Thebans with Julian Anderson’, Omnibus 76 (2018)

Rieu, E. Homer’s The Odyssey. London (2003)

Roberts, D. ‘Emily Wilson, trans. Homer: The Odyssey,’ Spenser Review 50.1.3 (2020)

Tracey, J. ‘The Complicated Radicalism of Emily Wilson’s The Odyssey’, Ploughshares at Emerson College (2018) https://blog.pshares.org/the-complicated-radicalism-of-emily-wilsons-the-odyssey/

Wilson, E. Homer’s The Odyssey, London (2018)

Wilson, E. Sebald Lecture, British Centre for Literary Translation (2019a)

Wilson, E. Sixth Annual Adam and Anne Amory Parry Lecture, Yale University (2019b)

Untranslatability of Imperialism: Exploring the Temporal Disconnect between Roman and Colonial Practices

This piece wishes to draw attention to the temporal disconnect between the contemporary terms of colonialism and imperialism and those of the provinces of the Roman Empire during the Julio-Claudian until the Nerva-Trajan dynasty, with a focus on the idea of the colony. As concepts having the same name can lead to overgeneralisation and homogenisation, it is important to note the disconnect between the two terms to ascertain proper agency to both the colonial subject of Empire and the Roman citizen in the colony. The terms as applied to modern imperialism and colonialism cannot be translated as a photocopy onto the Roman forms. Emily Apter calls this “untranslatability” in literary theory. A linguistic concept with its connotations that exists in one language may not exist in another and can thus not be translated. Lawrence Venuti takes this further and speaks of “cultural” translation and “linguistic” translation in his hermeneutic model of translating: a translation of a text, be it in whatever form (including concepts), becomes an independent text that cannot be equated to the ‘original’ text – this would be instrumentalism according to Venuti and would once again unjustly homogenise.

Imperialism is defined by Edward Said as “the practice, the theory, and the attitudes of a dominating metropolitan center ruling a distant territory” (Said (1994) 9), whilst imperialism in the Roman Empire did mean the deployment of Roman veterans to the annexed areas. This deploying sounds more like the modern conception of colonialism, where the coloniser settles within the land rather than ruling it from a centre point in the Empire. It is interesting then, to consider the definition – although debatable – of Roman colonialism. The settling of an actual colony was a status symbol and differentiated it from surrounding municipia and vici. Maureen Carroll points out that the biggest difference between the colonia and the other forms of settlement was the fact that those in the colony were Roman citizens (Carroll (2001) 43-44), even if they were not originally of Roman descent, such as the Ubians turned Agrippinenses (Huffman (2018)) in modern day Cologne. Being Roman would thus be a stamp rather than a complete shift in culture. This directly contrasts with the modern notion of colonialism, where the colony is utterly controlled by the coloniser to a point of internalisation of the coloniser’s identity and are in turn forcefully ‘Westernised’ and placed in a position of societal pressured mimicry of the Western identity (Bhabha (2004) 121-131). This would lead to fragmentation of identity and a ‘colonisation of the mind’. This is not at all seen in Roman colonialism, where archaeologists speak of ‘glocalisation’ rather than Romanisation, or having the agency to choose the adaptation of new cultural forms rather than having this forced upon them. The indigenous tribes of the provinces adopt Roman attributes, such as the style in which the gods are portrayed, but there is no evidence that culture got completely replaced (Carroll (2001) 120-122).

As has been discussed, there are serious differences between modern colonial and Roman practices of the concepts. With this, it can be argued that the terms are not translatable because of a temporal as well as historical disconnect between the two and thus the cultural translation creates two distinct forms of the concepts that cannot be used interchangeably. Doing so would take away agency from the tribes in the Roman provinces who performed ‘glocalisation,’ their voices would be swept under the rug by such a notion. To conclude, this short abstract of a longer piece with an archaeological case study of the Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensium hopes to give an insight into the unjust applicability of terms that, even though they may be etymologically similar, are not similar in their semantics nor meaning. It also hopes to draw attention to the fact that comparisons between such temporally displaced contexts cannot be done without considering Venuti’s hermeneutic model of translation, or else we get an untranslatable piece that disregards agency where it is due.

Yvonne Marinus

Utrecht University

Bibliography

Apter, E. ‘Untranslatability and the Geopolitics of Reading’, PLMA 134 (2019) 194-200.

Bhabha, H.K. ‘Of Mimicry and Men: The Ambivalence of Colonial Discourse’, in Bhabha, H.K. The Location of Culture. London (2004) 121-131.

Carroll, M. Romans, Celts & Germans the Provinces of Rome. Cheltenham (2001).

Coles, A.J. ‘Roman Colonies in Republic and Empire’, Brill’s Research Perspectives in Ancient History 3 (2020) 1-119.

Huffman, J. The Imperial City of Cologne: From Roman Colony to Medieval Metropolis (19 B. C. – 1125 A. D.). Amsterdam (2018).

Said, E. Culture and Imperialism. New York (1994).

Venuti, L. Translation Changes Everything: Theory and Practice. Abingdon (2013) 1-10.

Precious Metals at the Beginning and End of Jesus’ Life III: Silver

III: Judas’ Thirty Pieces of Silver

After looking at ‘magi gold’ and the ‘tribute penny’, perhaps the most famous numismatic episode in Jesus’ life comes during his final days. Before the Last Supper, Matthew 26:15 records Judas Iscariot going to the chief priests and agreeing to betray Jesus to them in return for ‘thirty pieces of silver.’

“And he said unto them, what will ye give me, and I will deliver him unto you? And they covenanted with him for thirty pieces of silver” (Matthew 26:15)

In Luke 22:3-6, the earliest Gospel, the details are slightly different, with the amount agreed between Judas, the chief priests and the temple guard officers not being recorded and seemingly not being paid up front.

“3 Then Satan entered Judas, called Iscariot, one of the Twelve. 4 And Judas went to the chief priests and the officers of the temple guard and discussed with them how he might betray Jesus. 5 They were delighted and agreed to give him money. 6 He consented, and watched for an opportunity to hand Jesus over to them when no crowd was present.”

It should also be noted that much like with the apocryphal Gospel of Thomas 100 recording the ‘tribute penny’ given to Jesus in Matthew 22:19 as being made gold rather than silver, the (possibly fifth or sixth century) Narrative of Joseph of Arimathea records Judas being paid 30 pieces of gold instead of silver.

There is little doubt that these ‘30 pieces of silver’ were coins – Matthew 26:15 uses the word ἀργύρια, argyria, simply meaning ‘silver coins’ – but there is nothing to suggest that they were all the same coin. Indeed, as mentioned in the previous pieces, there were several different types of silver coin in circulation in the Roman Near East of the first century AD.

As mentioned in our previous entry on the ‘tribute penny’, the most pervasive silver coinage at the time of Christ were Tyrian ‘shekels’ (really to be considered tetradrachms), which bore the Greco-Phoenician demigod, Heracles/Melqart.

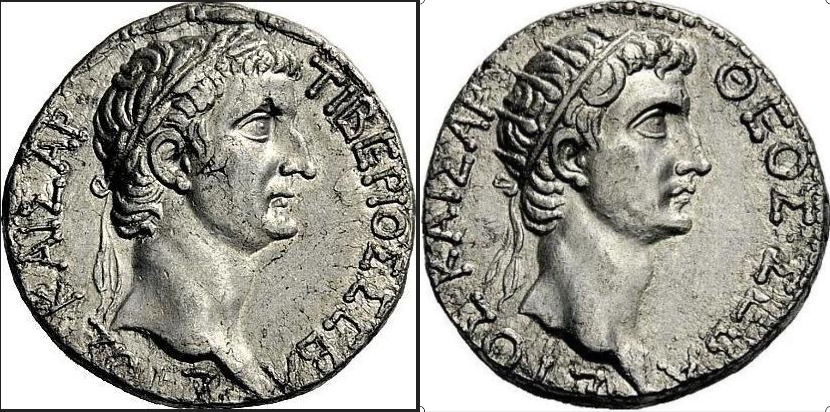

Other alternatives include Antiochene staters, which bore the head of Augustus, Ptolemaic tetradrachms of much less silver content and Tiberian denarii, which were much less widely circulated in the Roman east at this time.

Of all these potential options, Judas would certainly have wanted the majority (if not the entirety) of the ‘30 pieces of silver’ to be Tyrian ‘shekels’ as they had the highest silver content of them all – 94+% against 80% of the denarius, 75% of the Antiochene stater or a measly 25% of the Ptolemaic tetradrachm.

‘30 pieces of silver’ was something of a repeated idea of payment in books of the Bible. Exodus 21:32 has ‘30 shekels of silver’ as the recompense for an accidentally killed slave, while Zechariah 11:12 has Zechariah himself being paid ‘30 pieces of silver’ for his labour.

Could these combine to provide something of an indictment of Zechariah’s payment? Was his labour to be valued as no more than slave recompense? Then again Zechariah 11:13 considered his ‘30 shekels of silver’ to be a “handsome price”. Could there be some sarcasm here? Zechariah did immediately give the payment away, but as he did so by listening to the advice of the Lord and gave it “to the potter at the house of the lord,” it is unlikely that the prophet considered this payment to be miserly.

Indeed, there are some calculations (albeit using measurements from different times and places for similar, although not necessarily the same, coinage) that can be made to suggest what kind of value ’30 pieces of silver’ might have had, particularly around the time of Zechariah, considered to be the last quarter of the sixth century BC.

A century later, Thucydides III.17.4 recorded a drachma being a day’s pay for a skilled labourer, with the Athenian drachma – the most common standard of drachma at the time – weighing about 4g. If the ‘30 shekels of silver’ are to be taken as being the equivalent of tetradrachms, they would also be the equivalent of a payment of 120 drachmae or possibly four months’ wages. How much of this applies to the time of Jesus and Judas? The standard of the tetradrachm seems to have remained high, particularly the Tyrian ‘shekel’, which was in the mid/high 90% for silver content. But was a drachma considered a decent day’s pay for a skilled labourer in the mid-first century AD?

The full story of Judas’ ‘30 pieces of silver’ does give some idea of its value in the time of Jesus. Matthews 27:9 has Judas, filled with remorse, returning the ‘30 pieces of silver’ to the chief priests, before then hanging himself. The chief priests decided that they could not put the repaid ‘bounty’ into the temple treasury as it was now tainted with the blood of Jesus. They therefore used the money to buy a field which had originally been used by potters to collect high-quality clay for their ceramics. The chief priests turned this field into a burial plot for strangers, criminals and the poor, which became known as the Akeldama – Aramaic for ‘field of blood’ – and the ‘Potter’s Field’ for its original usage. This potters’ connection may be a link to the aforementioned donation by Zechariah, while Matthew also states that it was a fulfilment of a prophecy by Jeremiah, who is recorded buying a field in return for a payment of silver (Jeremiah 32:9 has the payment be 17 shekels of silver).

There could well be an idea in the purchasing of the potters’ field with the money used to buy the death of Jesus and its reuse as a ‘foreigners’ burial ground, that “Jesus’ death makes salvation possible for all the peoples of the world, including the Gentiles” (Blomberg in Beale and Carson (2007), 97).

The book of Acts 1:17-20 records a slightly different fate for not only Judas but also his ‘thirty pieces of silver.’ The Apostle Peter relates that Judas used his payment to buy a field, again linking to Jeremiah’s suggestion of silver being used to buy fields. Peter in Acts also states that in his newly bought field, Judas “fell headlong, his body burst open and all his intestines spilled out.” It is this field that Peter has becoming known as the Akeldama, in a fulfilling of Psalm 69:25 – “May their place be deserted; let there be no one to dwell in their tents.”

By the later Middle Ages, items associated with Jesus’ life had become big business in the world of relics and Christian iconography – the Spear of Longinus, nails from the crucifixion, the holy sponge, crown of thorns, Holy Grail – and a number of so-called ‘Judas pennies’ were presented as relics and were believed to help difficult cases of childbirth. The stone on which the coins were said to have been counted out for Judas was reportedly moved to the Lateran Palace in Rome.

To show the desire to find the so-called ‘Judas pennies’, a Syracusan decadrachm – much bigger than a Tyrian shekel/tetradrachm – which was held in the Hunt Museum in Limerick, Ireland was claimed to be one of the coins given to Judas. It is mounted in a gold frame, which is inscribed Quia precium sanguinis est – ‘This is the price of blood’. Other coins became associated with ‘Judas pennies’, such as those of Rhodes that depicted the sun god Helios with the rays of light being projected from his head interpreted as the Crown of Thorns.

Two places that ‘30 pieces of silver’ definitely went were into the modern parlance as a phrase to describe the price for which a person might sell out or betray another, while the subject of Biblical perfidy on the promise of financial gain provided many artists of the Renaissance and beyond with inspiration for their works.

Bibliography

Blomberg, C.L. ‘Matthew’, in Beale, G.K. Beale and Carson, D.A. Carson (eds.), Commentary on the New Testament Use of the Old Testament. Grand Rapids (2007) 1-110

Cherry, J. and Johnston, A. ‘The Hunt Dekadrachm’, AJ 95 (2015) 151-156

Marotta, M.E. ‘So-called ‘Coins of the Bible’ (2001) https://web.archive.org/web/20020618223339/http://coin-newbies.com/articles/bible.html

Yeoman, R.S. Moneys of the Bible. New York (1982)

Censeris Caesar: Yet Another British Imperial Pretender or a Mixed-up ‘Carausius II’?

In all the numismatic discussions of ‘Carausius II’, who he might have been and when he might have attempted to rule, there is another potential individual who is somewhat overlooked. Found amongst a group of about 400 coins at Richborough was an issue with the obverse legend of DOMINO CΛ.. (ENSERIS, taken to mean Dominus Caesar Censeris/Genseris.

This would seem to posit another man of imperial position in Britain in a similar period as ‘Carausius II’, with the coins of both men sharing an “intimate connexion” (Pearce (1928), 364; cf. Salisbury (1926), 312 figs.1-2).

The main basis of that ‘connexion’ is type. Looking at the ‘Censeris/Genseris’ coin, its reverse legend is largely illegible, but while Pearce (1928), 364 suggests that what can be seen is not the letters of FEL TEMP REPARATIO, the ‘Censeris/Genseris’ issue does host a ‘Fallen Horseman’. This means that it is similarly based on the ‘Fallen Horseman’ FEL TEMP REPARATIO type as the vast majority of the ‘Carausius II’ coins.

This also means that chronologically placing ‘Censeris/Genseris’ is beset by the same issues as with ‘Carausius II’ and indeed follows the same development – initially he was seen as an early fifth century usurper from the time of Constantine III, only to later be moved to the 350s, during the reign of Constantius II. And “in the light of studies of the internal chronology of the FEL TEMP REPARATIO coinage, it is possible to isolate the production of the Carausius and Censeris copies to the years 354-8” (Casey (1994), 160).

Without going into too much repetitive detail on the coin’s detail, like ‘Carausius II’, ‘Censeris/Genseris’ is inscribed with the titles of ‘Lord’ and ‘Caesar’. Again DOMINO is a peculiar, and indeed, poor Latin declension, likely highlighting the local origin of the coins.

This chronological, geographic and numismatic similarity also sees all the same political questions asked about ‘Censeris/Genseris’ – was he a local secessionist like the first Carausius? Was he a rebel against Magnentius through loyalty to Constantius II? Or a local usurper orchestrated by the regime of Constantius?

All of these questions face the same arguments – dating of the coin types removing Magnentius as a direct factor, Constantius unlikely to have signed off on a local usurpation etc. – and the same lack of definitive answer about the identity and even existence of ‘Censeris/Genseris’…

However, there is one major avenue of difference to contend with in dealing with ‘Censeris/Genseris’ in comparison with ‘Carausius II’: what appears to be the rather obviously different name. The choice to receive the ‘(’ as either a ‘C’ or a ‘G’, rendering it ‘Censeris’ or ‘Genseris’ could have significant ethnic consequences for the depiction of this man.

Following the ‘C’ route, Anscombe (1927-1928), 9 contended that the legend on the ‘Censeris’ coin found at Richborough read DOMINO CENS-ΛVRIO CES “and that it should be regarded as dedicatory, and be expanded and normalized as follows: DOMINO CENSORIO CAESARI.”

Despite seeming to be a good Roman name, ‘Censorius’ appears a little less frequently amongst Roman sources than might be expected. Under the Roman Republic, the similar ‘Censorinus’ was a more popular name, being a cognomen for the plebian gens Marcia. This was a family whose members that held all the major offices of state, including the censorship, where their name came from. There were also some Censorini who acted as moneyers, immortalising their name on coins. Several of them were also friends and enemies of many of the prominent men in the Fall of the Republic.

During the reign of Claudius II (268-270), there was reputedly a usurper in Italy called Censorinus, who only lasted a few days before being executed by his soldiers (SHA Tyranni Triginta 33). While this Censorinus seemingly being a complete fabrication by the writer(s) of the Historia Augusta (Barnes (1978), 69; Rohrbacher (2016), 118; Syme (1968), 157) might seem to nullify him as an example, the fact that the fourth century Historia Augusta uses that name in a fabrication might hint at some popularity for that name in Late Antiquity.

As for ‘Censorius’ specifically, the most prominent late antique examples are both from the fifth century. The comes Censorius playing a prominent role in Romano-Suebic relations in Spain during the 430s, which is recorded in the Chronicle of Hydatius, while the Life of St Germanus, written by Constantius of Lyon, was addressed to Censorius, bishop of Auxerre.

There are also versions of the name in Romano-British inscriptions (CIL VII.1336, 289 and 291), and while it is not dateable, there is an altar of Marcus Censorius Cornelianus, who, while a native of Gallia Narbonensis and a centurion of the Legio X Fretensis, found himself in Britain, specifically Uxellodunum, near what is now Maryport in Cumbria. This would suggest service along Hadrian’s Wall, possibly as praepositus of the I Hispanorum cohort (RIB 814; CIL VII.371). There are other similar names recorded at Chichester, Caerleon and elsewhere (Anscombe (1927-1928), 10).

Anscombe (1927-1928), 10 commented that of all these Late Roman ‘Censorius’ and similar names, “not one indicates an official of high status… as is demanded for “Censaurius Cesar””. However, this is not the empire of the first or second century – if the military crisis of the third century had revealed anything, it was that a man of any background could see himself elevated to empire. So, the idea that there are few or no ‘Censorius’ of high rank known of in Late Antiquity is really of no consequence. The only benefit to be gleaned from this collection of men and women named ‘Censorius’ or similar is that it shows that the name was in circulation in western Europe and specifically Britain during the period that ‘Censaurius Cesar’ may have attained some imperial power.

Anscombe (1927-1928) also goes to significant etymological, historiographical and even mythological lengths to connect his ‘Censaurius Cesar’ to characters who appear in various historically based legends, such as Arthur and Beowulf. Not only does this stretch the bonds of credibility, it would also seem to be based on the initial chronology of Evans (1887), pre-eminent at the time of Anscombe’s writing, that deposited ‘Censaurius Cesar’ in the first decade of the fifth century, rather than the 350s.

But what if the ‘(’ was meant to be a ‘G’, and the man on the Richborough coin was actually ‘Genseris’? Such a name looks decidedly Germanic in origin, with the most famous, similar name would be Geiseric, king of the Vandals (428-477), a name which is also recorded as either ‘Gaiseric’ or ‘Genseric’. The change in this name from something like the more Germanic ‘Gaisaris’ to ‘Genseris’ could be due to Roman pronunciation and then spelling of the Germanic original or possibly an inscribing error (Stevens (1956), 348-349).

But why would a potential Roman usurper have a German name in mid-fourth century Britain? It might have seemed to make more sense when this whole episode of ‘Carausius II’ and ‘Genseris’ was thought to have taken place in the first decade of the fifth century when Germanic tribes were menacing Roman territory in significant numbers and settling in parts of Britain with increasing frequency. The redating of this episode to the mid-350s lessens this impact somewhat, but then there were Vandals and Burgundians settled in Briain under the emperor Probus in c.277/278 (Zosimus I.68.3).

There is another linguistic suggestion for the origin of ‘Censeris/Genseris.’ Could it be that local dialects, scribal errors and political expedience have corrupted ‘Censeris/Genseris’ into something like Carausius? (Stevens (1956) 348-349) As was seen in the previous ‘Carausius II’ piece, given the number of mistakes made with it, ‘Carausius’ seems to have been a difficult name to inscribe – CARAVƧIO, (ARVƧI etc. (so seemingly was ‘Constantius’: CONTA, (OHTATI, (ONSTAN, (ONSTATI, CONXTA[NTI]NO)

Could it be that the original ‘Carausius’ was corrupted to ‘Ceris’, then to ‘Censeris/Genseris’ (Evans (1887), 197 n.9) and then possibly back to ‘Carausius’ when the corrupted forms did not look ‘Roman’ enough for someone claiming an imperial position?

This would suggest that ‘Carausius II’ and ‘Censeris/Genseris’ were in fact the same person. On top of some potential linguistic connection, their coins sharing the same base type, influences and time period. The smaller number of so far discovered ‘Ceneris/Genseris’ coins in comparison to ‘Carausius II’ could hint at a single usurper changing his name from a Latin/Germanic name to a more obviously Romano-British imperial name.

However, this comparative paucity of ‘Censeris/Genseris’ coins might actually work to detach him from ‘Carausius II’; his lower numismatic output possibly suggesting that he was a shorter-lived predecessor or successor of ‘Carausius II’.

One could possibly invoke the numismatics of another regional Roman revolt that took place over 250 years later – that of the Heraclii in Africa. It was initially focused on Heraclius the Elder, the exarch of Carthage, only for his son, also Heraclius, to take the active role in claiming the imperial throne for himself in 608-610. The Elder then died not long after hearing news of his son’s accession, reducing the number of coins he appears on.

Could we be seeing something similar here with ‘Censeris/Genseris’ being a colleague, even relative of ‘Carausius II’ who was sidelined for some reason? Early death? Defeat by local forces? Or perhaps he was raised to power by ‘Carausius II’ later as a colleague/successor, only for the regime to collapse before many coins could be minted of him?

This idea of a familial connection between ‘Censeris/Genseris’ and ‘Carausius II’ permeates interpretations of British folklore, particularly with the attempts to connect this second Carausius with the first British imperial ruler of that name.

In chronological terms, such a direct connection between Carausius and ‘Carausius II’ is not out of the question. With Carausius having been killed in 293, any son he fathered would had to have been at least 61 years old by 354: not old enough to be ruled out, and also easily old enough to have a son…

Some mythological interpretations saw one of the sons of Carausius and Oriuna Wledic being named ‘Genseris’ – do we have the makings of a family tree?

As fun as it may be to draw family trees, this is entirely fanciful stuff (the Constantinian dynasty is frequently shoehorned into this Carausian/Oriunan mess) and as we saw last time with ‘Carausius II’, the entire existence of a woman named ‘Oriuna’ being the wife of Carausius stems from a numismatic misinterpretation.

Furthermore, all of this speculation about a Latin ‘Censeris’, Germanic ‘Genseris’, a garbled ‘Carausius’ or a father/son succession is just that – speculation; as is any attempt to posit a role for ‘Censeris/Genseris’ in the political machinations of Constantius II and Magnentius.

Indeed, the redating of their coins to 354-358, and the silence of the sources, particularly Ammianus, not only detach ‘Carausius II’ and ‘Censeris/Genseris’ from the events of Magnentius’ usurpation, they are as damaging to the actual existence of ‘Censeris/Genseris’ as they are ‘Carausius II’.

75 years ago, Stevens (1956), 349 suggested that the whole story of ‘Censeris/Genseris’ (and by extension ‘Carausius II’) was still “more for the historical novelist than for the historian”, but with the hope that future research would expand upon the historical speculation of such novels into something akin to proper history. Unfortunately, this has not been the case. While there has been some limited growth in the supposed reach of ‘Carausius II’ with the discovery of more of his coins, ‘Censeris/Genseris’ remains a character as shrouded in mystery and doubt as he was in the 1950s.

Bibliography

Anscombe, A. ‘The Richborough coin inscribed DOMINO CENSAVRIO CES,’ BNJ2 9 (1927-1928) 1-23

Barnes, T.D. The Sources of the Historia Augusta. Brussels (1978)

Casey, P.J. Carausius and Allectus: The British Usurpers. London (1994)

Evans, A.J. ‘On a coin of a second Carausius, Caesar in Britain in the fifth century’, NC 7 (1887) 191-219

Kennedy, J. A Dissertation Upon Oriuna, Said to be the Empress, or Queen of Emngland, the Supposed Wife of Carausius, Monarch and Emperor of Britain. London (1751)

Pearce, J.W.E. ‘A new coin from Richborough,’ Ant. J. 8 (1928) 364-365

Rohrbacher, D. The Play of Allusion in the Historia Augusta. Madison (2016)

Salisbury, F.S. ‘A new coin of Carausius II,’ Ant. J. 6 (1926) 312-313

Stevens, C.E. ‘Some thoughts on “second Carausius”’, NC5 16 (1956) 345-349

Stukeley, W. ‘Oriuna, wife of Carausius, Emperor of Britain,’ Palaeographia Britannica: Or, Discourses on Antiquities in Britain. Number III. London (1752)

Sutherland, C.H.V. ‘Carusius II, “Censeris”, and the barbarous Fel. Temp. Reparatio overstrikes’, NC5 5 (1945) 125-133

Syme, R. Ammianus and the Historia Augusta. Oxford (1968)

Precious Metals at the Beginning and End of Jesus’ Life II: ‘Render Unto Caesar’

Looking at the possibilities of what any numismatic golden gift that Jesus might have received as a newborn might raise questions about the other coins connected to events in his life. On top of the ‘Cleansing of the Temple’ (known by some as the ‘Temple tantrum’), where Jesus looked to eject moneychangers from the vicinity of the Temple in Jerusalem, there are two other very famous incidents to take place late in Jesus’ life that involved coins.

The first of these comes in Matthew 22:15-22…

15 Then the Pharisees went and plotted to entrap him in what he said. 16 So they sent their disciples to him, along with the Herodians, saying, “Teacher, we know that you are sincere, and teach the way of God in accordance with truth, and show deference to no one; for you do not regard people with partiality. 17 Tell us, then, what you think. Is it lawful to pay taxes to the emperor, or not?” 18 But Jesus, aware of their malice, said, “Why are you putting me to the test, you hypocrites? 19 Show me the coin used for the tax.” And they brought him a denarius. 20 Then he said to them, “Whose head is this, and whose title?” 21 They answered, “The emperor’s.” Then he said to them, “Give therefore to the emperor the things that are the emperor’s, and to God the things that are God’s.” 22 When they heard this, they were amazed; and they left him and went away. (Matt. 22:15-22, NRSV; cf. Mark 12: 13-17; Luke 20: 20-26)

As seen here, the text identifies the coin given to Jesus as a denarius (more accurately, given the New Testament’s Greek, δηνάριον – dēnarion); however, in the original King James Version of the Bible, the coin was referred to as a ‘penny’, which has given rise to it being called the ‘tribute penny’ (As an interesting aside, this connection between the denarius and the penny seems to form the basis for the abbreviation of ‘d’ being used as meaning ‘pence’ in British numismatic parlance until the 20th century, not to mention the continued linguistic influence of denarius on several modern words for ‘money’ – denaro, denar, dinheiro, dinero, as well as being the basis for dinar).

In the apocryphal Gospel of Thomas 100, the coin given to Jesus is made of gold, raising all the same questions as the ‘magi gold’ in terms of its identification, with the added suspect of it being an aureus of Tiberius.

The King James translation also gives this episode in Jesus’ life the more famous tagline used as the title of this piece – “Render unto Caesar”, a reduction which perhaps obscures some of the potentially more nuanced meanings involved in Jesus’ pronouncement.

However, our focus here is on the identification of the coin itself. The denarius already had a long history by the early first century AD, having been originally minted in around 211BC during a major overhaul of Roman coinage during the Second Punic War.

Its name comes from its initial value of 10 asses, with an as being a bronze (and later copper) coin introduced in c.280BC – denarius literally means ‘containing ten’, and while it was re-tariffed in 141BC to being the equivalent of 16 asses (reflecting the decrease in weight of the as), the name stuck and the denarius became the backbone of much of the Roman numismatic economy throughout the remainder of the Republic and on into the Early Imperial period.

This prolonged history of issue would seem to provide a considerable number of potential coins being referred to here as the ‘tribute penny.’ However, the description provided by Jesus and the Pharisees of this δηνάριον can reduce the chronological scope considerably. The mention of ‘Caesar’ as being depicted on the coin means that it came from the period of Julius Caesar’s minting of denarii with his own head in the mid-40s BC and after.

Given that he was emperor at the time of this proposed numismatic confrontation between Jesus and the Pharisees, it is usually thought that the ‘tribute penny’ was a denarius of Tiberius (14-37AD).

And as it seems that Tiberius only issued one type of denarius during his reign with the inscription of TI CAESAR DIVI AVG F AVGVTVS (‘Tiberius Caesar Augustus, son of the Divine Augustus’) around his head on the obverse and a female figure seated on a chair. The figure is of uncertain identity but is sometimes considered to be Tiberius’ mother Livia in the guise of the divine Pax.

However, while the Tiberian identification might seem most likely, it is not certain. As mentioned, ‘Caesarian’ denarii had been produced for nearly 80 years by the time of this Pharisaic attempt to trap Jesus. In that time, various coins were in circulation that could fit the description of a coin sporting the head of ‘Caesar’ and ‘his’ inscription.

Not only did Julius Caesar mint coins with his own head on them, others also minted coins depicting him after his assassination. And given his eastern area of influence in the 30s BC, could the coin handed to Jesus have been issued under Mark Antony as a posthumous tribute to Julius Caesar? Antony certainly minted coins with his own and Caesar’s heads on them in 43BC.

Of course, the name ‘Caesar’ need not mean Julius Caesar himself. Some of Antony’s coins depicted his then ally Octavian i.e. ‘Gaius Julius Caesar’, and as the future Augustus took ‘Caesar’ as his name, it became attached to the imperial position and the ruling family.

The numismatic ‘Caesar’ therefore takes in not only Julius Caesar and then Augustus and Tiberius, but also numerous other members of the Julio-Claudian dynasty. Under the first two emperors, as well as their own, there were also denarii minted bearing the likenesses of Augustus’ grandsons, Gaius and Lucius (this has been suggested as the most “statistically likely” ‘Caesarian’ denarius to have been placed in Jesus’ hand; Marotta (2001)), and Tiberius’ nephew, Germanicus, who was prominent in the eastern provinces. It is clear then that the identity of ‘Caesar’ in the Gospels and therefore the denarius in question ranges much wider than merely the ruling emperor at the time of Jesus’ numismatic conversation with the Pharisees.

When is a δηνάριον not a denarius?

However, there is room to widen the potential range of identities of this ‘tribute penny’ even further. This is because while on the surface the identification of the coin handed to Jesus as a δηνάριον and therefore a Roman denarius seems set in stone, this is actually not the case.

Numismatic investigation suggests that there were very few denarii in Jerusalem (or even Syria for that matter) at the time of Jesus (Ariel (1982)), severely curtailing the chances of the ‘tribute penny’ actually being a denarius. But then why would the Gospel writers identify it as such?

As the Evangelists (focus usually falls on Mark as the widely accepted earliest Gospel writer) were writing some years after the events of Jesus’ life, it could be that the appearance of a denarius in the conversation between Jesus and the Pharisees is a little anachronistic, with Mark and the other Gospel writers projecting the numismatic normality from their period back to that of Jerusalem in the 30sAD. And even if the denarius was still not all that normal in their time, the Evangelists could be presenting it as such in order to cater to their increasingly Romanised audience.

So what might the Evangelists have been ‘mistaking’ for a δηνάριον? Almost certainly an inscribed silver coin of similar size which depicted a ‘Caesar’ of some sort and there are some candidates.

Antioch issued tetradrachms which had a ‘Caesar’ on both sides – Augustus and Tiberius – and an imperial inscription. The Augustan inscription does call him ‘theos’ – a ‘god’, which would clearly be heavily objected to by the Jews in the same manner as their objecting to the Tiberian denarii sporting the inscription DIVI AVG F, depicting Tiberius as the ‘son of the Divine Augustus’. But could such blasphemous coins seeping into Judaea be part of the reason for the moneychangers setting up in the environs of the Temple in Jerusalem – to keep out such ‘graven images’ and profane declarations? Or had the temple always accepted just Tyrian ‘shekels’ and keeping such blasphemous tetradrachms and denarii were merely an extension of the money-changers normal work?

The size of this tetradrachm could also be a help or a hindrance to it being identified as the ‘tribute penny.’ It is twice the size of a denarius, which makes mistaking it for one less likely, but this size (and the busts and inscriptions) would make it a useful prop for the Jesus vs Pharisees encounter (Lewis (1999), 3-13; Lewis and Holden (2002), 19) [There was another Tiberian tetradrachm from Antioch that had the Tyche of Antioch on the reverse (RPC I.4162), which followed similar issues of Augustus (RPC I.4150-60)].

Another numismatic option would be the series of silver drachmae issued from Cappadocian Caesarea issued during the reign of Tiberius, featuring several different Caesars – Tiberius himself, the divine Augustus, Tiberius’ adopted son and heir, Germanicus, and Tiberius’ actual son, Drusus.

These Tiberian drachmae come in somewhat varied weights, but while the Tiberian denarius averages out at slightly heavier, there is enough similarity in weight to make a ‘mistaking’ of these drachmae for denarii realistic. Those depicting Augustus would also have come with the ‘graven images’ issue as Augustus is being presented as a divine being.

Perhaps the most ubiquitous silver coinage in Judaea by 30AD – the Tyrian shekel – would be available to be used an exhibit in the Jesus/Pharisee confrontation, particularly given its acceptance for the Jewish Temple tax. However, this coin is also considerably bigger than the denarius, as it was considered by the Greeks to be the equivalent of the tetradrachm. And while the Tyrian shekels of this period did have an inscription on them, it had nothing to do with the emperor and none of the coins depicted any kind of ‘Caesar’, instead bearing the Greco-Phoencian demigod, Heracles/Melqart (RPC I.4632-66): a strange choice of coin to be allowed for use in the Jewish Temple [Sidon half-shekels would be closer in size to a denarius, but are far less ubiquitous and feature Tyche, rather than a ‘Caesar’; RPC I.4559-60].

As we can see, there are numerous obstacles in the way of a firm identification of the so-called ‘tribute penny’ – size, ubiquity, numismatic content, chronology – None of which, individually or collectively, rule out any of the candidates presented here conclusively…

Bibliography

Ariel, D.T. ‘A Survey of Coin Finds in Jerusalem’, Liber Annuus 32 (1982), 273-326

Lewis, P.E. ‘The actual Tribute penny’, JNAA 10 (1999), 3-13

Lewis, P.E. ‘The Tribute penny in the Gospel of Thomas’, JNAA 10 (1999), 13-21

Lewis, P.E. and Bolden, R. The Pocket Guide to Saint Paul: Coins Encountered by the Apostle on His Travels. Kent Town (2002)

Marotta, M.E. ‘Six Caesars Of The Tribute Penny’ https://web.archive.org/web/20111012091846/http:/coin-newbies.com/articles/caesars.html

Shore, H. ‘The Real ‘Tribute Penny’’, Celator 10 (1996), 16-18

Yeoman, R.S. Moneys of the Bible. New York (1982)

For a succinct look at this ‘tribute penny’ debate and the potential candidates, check out this video by Professor Kevin Butcher (University of Warwick) – ‘Render Unto Caesar’.

300 Spartans (1962) and the Battle of Thermopylae

O stranger, tell the Lacedaemonians that

we lie here, obedient to their words.

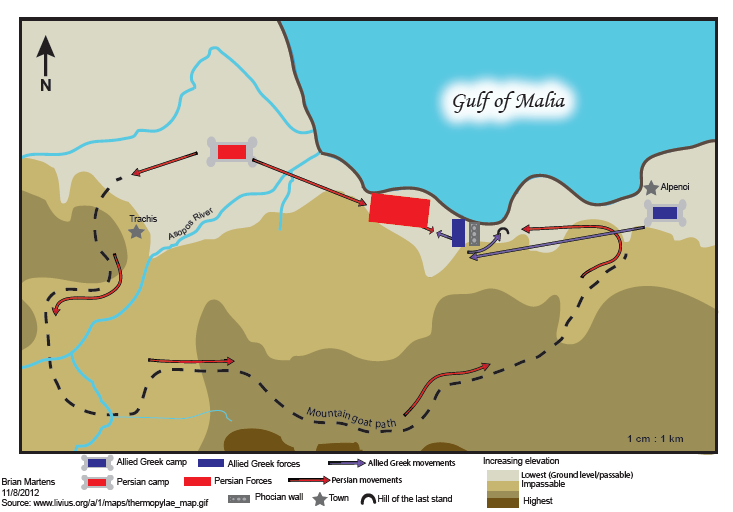

We all know the story of the Battle of Thermopylae, right? (right?!?) – 2,501 years ago in 480BC, having been foiled first by the weather and then the Athenians (and Plataeans) at Marathon, the Persians, under Xerxes, tried again to invade and conquer Greece. This time they brought an enormous army and fleet to bear on the usually disunited poleis of Greeks. Putting aside enough of their differences, a small (but not that small) Greek force squared up to the mighty Persian host at the narrow pass of Thermopylae, where three days of slaughter saw the annihilation of its Sparto-Thespian core in the name of buying time for the defence of their Greek homeland, taking 20,000 Persians with them into the afterlife.

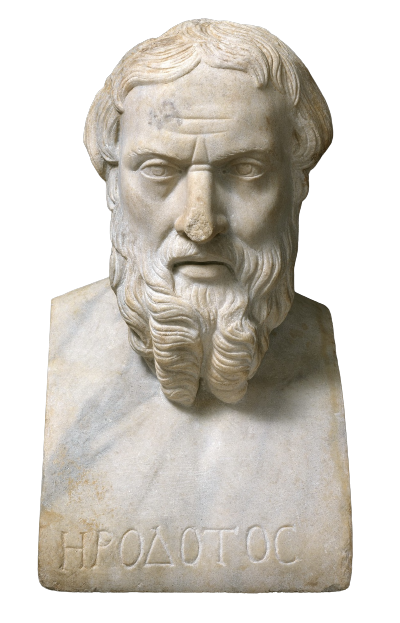

With its themes of heroic persistence and sacrifice, loyalty and betrayal to name but a few, it is perhaps the most evocative story of the Ancient World and it was this historical tale recorded by the likes of Herodotus, Diodorus Siculus and others that was turned into a screenplay by George St. George and transferred to the big screen by 20th Century Fox and Polish-Hungarian-American director Rudolph Mate.

The resultant 1962 film 300 Spartans was made right in the middle of the era of the great Hollywood historical epics – Quo Vadis (1951); Ben Hur (1959); Spartacus (1960); Cleopatra (1963) – and its ‘sword-and-sandal’ subgenre in mostly Italian cinema (perhaps most famous for its poor English dubbing and eventual production of the ‘spaghetti western’).

However, 300 Spartans does not really belong to either of these groups. It was originally planned to be a ‘sword-and-sandal’ production with a concomitant lower budget, but the cooperation of the Greek government saw the budget expanded to around twice that of the usual ‘sword-and-sandal’ level. That said, even this expanded budget still paled in comparison to the money being thrown into the Hollywood epics of the time. To put things in perspective, the $1.35 million used to make 300 Spartans was around 10% of the budget for Spartacus and less than 4.5% of that of Cleopatra…

Under the working title of ‘Lion of Sparta’, what became 300 Spartans was filmed in Cinemascope in Greece, although not at the site of Thermopylae, likely due to the original site changing considerably due to the receding coastline. Instead, it was shot at the village of Perachora and around Lake Vouliagmenis, north of Corinth. On top of the listed cast (several of whom were experienced Greek actors), some 1,100 Royal Hellenic Army soldiers were used as extras, along with numerous locals and their animals (particularly for the mass of the Persian army).

As well as being perfect fodder for the cinematic trends of the time, the telling of the story of the Battle of the Thermopylae in the early 1960s has also been taken to reflect a political message on the background of the Cold War – ‘defenders of western freedom’ vs ‘the evil eastern empire’, but despite that, the film was a great success in Russia.

And why not?

The film manages to convey much of what is perhaps one of the most spectacular historical events of the Ancient World – heroic self-sacrifice against overwhelming odds and internal betrayal, comradery between men fighting side by side, religion and politics getting in the way of the fight for freedom, or the contrast between good (Greek) leadership and poor (Persian) leadership… 300 Spartans even adds in a couple of other literary/cinematic tropes of its own to the story with Artemisia positioned as the ‘deceptive woman’, working to bring down a ‘great man’ and a romance angle in the Greek ranks.

As you can imagine with a cinematic recreation of an historical event, there are some factual issues with 300 Spartans. I am not going to be overly critical, but it is worth having a look at some of its missteps, as well as some of the things that it did well.

At the outset, 300 Spartans presents a rather ‘Greece is Athens’ opening, as the establishing shots of Greece are all of the major sights in Athens. That said, while the Eurotas valley presents a picturesque scene, the remains of ancient Sparta or the Pass of Thermopylae are not exactly recognisably ‘Greek’ as the skyline of modern Athens.

The Persian Army of Xerxes (According to Herodotus…)

| 1,207 triremes with 200-man crews: Phoenicians along with “Syrians of Palestine”, Egyptians, Cyprians, Cilicians, Pamphylians, Lycians, Dorians of Asia, Carians, Ionians, Aegean islanders, Aeolians, Pontic Greeks | 241,400 |

| 30 marines per trireme from the Persians, Medes or Sacae | 36,210 |

| 3,000 Galleys, including 50-oar penteconters (80-man crew), 30-oared ships, light galleys and horse-transports | 240,000 |

| Total of ships’ complements | 517,610 |

| Infantry from 47 ethnic groups: Medes, Cissians, Hyrcanians, Assyrians, Chaldeans, Bactrians, Sacae, Indians, Arians, Parthians, Chorasmians, Sogdians, Gandarians, Dadicae, Caspians, Sarangae, Pactyes, Utians, Mycians, Paricanians, Arabians, Africa Ethiopians, Ethiopians of Baluchistan, Libyans, Paphlagonians, Ligyes, Matieni, Mariandyni, Cappadocians, Phrygians, Armenians, Lydians, Mysians, Asian Thracians, Lasonii, Milyae, Moschi, Tibareni, Macrones, Mossynoeci, Mares, Colchians, Alarodians, Saspirians and Red Sea islanders. | 1,700,000 |

| Horse cavalry from the Persians, Sagartians, Medes, Cissians, Indians, Caspians and Paricanians. | 80,000 |

| Arab camel troops and Libyan charioteers | 20,000 |

| Total Asian land and sea forces | 2,317,610 |

| 120 triremes with 200-man crews from the Greeks of Thrace and the islands near it. | 24,000 |

| Balkan infantry from 13 ethnic groups: European Thracians, Paeonians, Eordi, Bottiaei, Chalcidians, Brygians, Pierians, Macedonians, Perrhaebi, Enienes, Dolopes, Magnesians, Achaeans | 300,000 |

| Total | 2,641,610 |

It is not surprising that 300 Spartans leans into the historical record of Herodotus VII.60-61, 87, 184-185 on the size of the Persian army that invaded Greece as it builds up the ‘Big Bad’ that the heroic Spartan-led Greeks had to face down. That said, the more likely number of around 150,000 Persians crossing the plains of Thessaly and looking to force the Pass of Thermopylae was still the largest army than Greece had ever seen.

As for the Greek army, despite its title and a lot of its Lacedaemonian focus, 300 Spartans does not try to suggest that it was Persians vs only Spartans at Thermopylae. The Phocians defending the goat trail in the mountains are mentioned, as is the prominent roles of Demophilus and his Thespians, including their volunteering to remain behind in the pass with the Spartans in order to facilitate the escape of the rest of the army (a Theban force of 400 men was forced to stay behind too as they were thought to be on the verge of defecting, but this is not depicted in the film). Much of this Greek army – c.7,000 in total – is not shown in the movie, but it, along with the Greek fleet operating off the coast in the Malian Gulf, is in a way personified in the Athenian general, Themistocles (who was a little more friendly with the Spartans than history would suggest…).

The film even shows that the Spartan force of Leonidas itself was not solely made up of Spartans, as it has some non-hoplites working and then fighting alongside them. As these men were acting as dogsbodies for the Spartans, there were almost certainly intended to be helots (although the film perhaps does not present enough of them).

Of course, the most famous number involved with the Battle of Thermopylae is that of the ‘300 Spartans’ themselves. But this number comes with some warnings. As the Spartan force was made up of Leonidas and his 300-strong guard, it was initially ‘301 Spartans’, something that the film (accidentally?) references with Phyllon being recognised as the 301st Spartan at Thermopylae. Circumstances would then allow Phyllon’s father, Grellas, to fight alongside Leonidas, so the film actually has 302 Spartans fighting at Thermopylae.

As well as being the ‘301st Spartan’ and the focus of a love story, Phyllon is also used to depict the fact that not all Spartans who marched to Thermopylae actually died there. After being injured in one of the engagements with the Immortals, Phyllon is order by Leonidas to retire through the rear of the battlefield – Phyllon’s place was taken by his father Grellas, who was proven to not have betrayed Sparta as was thought, redeeming the honour of both himself and his son (the film does seem to forget to show Phyllon actually escaping with Ellas, but it is mentioned in passing that the rest of the Greek army had been able to retreat).

Out of the initial 301 who made up the Spartan force at Thermopylae, two are known to have survived the collapse of Leonidas’ position in the wake of the Immortals forcing of the mountain pass. They are named as Aristodemus and Pantites. The latter was not present at the last stand because Leonidas had sent him on an embassy to Thessaly and he had not made it back in time. Finding himself in disgrace at Sparta, Pantites later hanged himself (Herodotus VII.232).

Aristodemus was not present at the last stand due to being sent home by Leonidas as he had some kind of eye infection (Hogewind, B.F., Coebergh, J.A.F., Gritters-van den Oever, N.C., de Wolf, M.W.P and van der Wielen, G.J. ‘The ocular disease of Aristodemus and Eurytus 480 BC: diagnostic considerations’, International Ophthalmology33 (2013) 107-109 suggested that it may have been the result of ingesting berries of the atropa belladonna plant – deadly nightshade). Such an illness leading to his excusing from fighting would likely not have reflected poorly on Aristodemus (Herodotus VII.229) had it not been for the actions of another victim of this eye infection – Eurytus. He too was excused from combat by Leonidas and together he and Aristodemus began the journey back to Sparta; however, upon hearing of the Persian forcing of the mountain pass and encirclement of the Spartan position, the largely blind Eurytus had his helot attendant lead him back to the battle, where he was killed.

Had Eurytus returned to Sparta with Aristodemus, neither are likely to have faced any sort of legal condemnation – they were after all following the orders of their king (but then Pantites had been too…). However, because Eurytus did turn back and died in combat, Aristodemus was condemned as a coward: “no man would give him a light for his fire or speak to him; he was called Aristodemus the Coward” (Herodotus VII.232). Aristodemus only removed this black mark of cowardice by throwing himself into the fighting at the Battle of Plataea, fighting (and dying) like a man possessed (Herodotus IX.71).

The ‘300’ Spartans… And Others…

| Herodotus VII.202-203 | Diodorus Siculus XI.4 | |

| Lacedaemonians/ Perioeci/helots | 900? | 1,000 (including 300 Spartans) |

| Spartan hoplites | 300 | – |

| Mantineans | 500 | 3,000 (other Peloponnesians sent with Leonidas) |

| Tegeans | 500 | |

| Arcadian Orchomenos | 120 | |

| Other Arcadians | 1,000 | |

| Corinthians | 400 | |

| Phlians | 200 | |

| Mycenaeans | 80 | |

| Total Peloponnesians | 3,100 or 4,000 | 4,000 or 4,300 |

| Thespians | 700 | – |

| Malians | – | 1,000 |

| Thebans | 400 | 400 |

| Phocians | 1,000 | 1,000 |

| Opuntian Locrians | “All they had” | 1,000 |

| Grand total | 5,200 (or 6,100) plus Opuntian Locrians | 7,400 (or 7,700) |

In reality, we have no way of knowing exactly how many Spartiates actually lined up to fight at the ‘Hot Gates’ – did all 301 who set out from Sparta make it to the battlefield? In the film, the arduousness of the journey was suggested in the difficulties both Ellas and Phyllon got into following the Spartan column. It would seem though that of the 301 Spartans to march to Thermopylae, only two survived the battle.

I must admit that upon viewing 300 Spartans recently that I was immediately struck by its depiction of the tactics used at the Battle of Thermopylae. In my mind’s eye, the fighting was not so out in the open; much more of the Persians trying to take a fortified position. But it does seem that the pass of Thermopylae was about 100 m wide and that at least some of the Greek force were stationed in front of the Phocian wall, which may seem a little strange given the recognition of its tactical usefulness in its rebuilding (reflected in the film), but it does seem to be historically accurate (cf. Herodotus VII.208, 223).

Given its necessarily limited run time, 300 Spartans reduces the combat at Thermopylae to a small number, almost just daily, Persian attacks on the Greek position, when instead the fighting “lasted all day” (Herodotus VII.210.2). The film also takes dramatic license with most of the manoeuvres, tactics and ruses de guerre employed by Leonidas and his men in order to add variety to the battle depiction. There is no mention of a Greek raid on the Persian camp prior to the battle, nor any preparing of the pass to use fire to hem in the Persian infantry or recognising and repelling of a Persian cavalry attack. Aside from their defensive position and the possibility that they employed some form of the phalanx – “the men stood shoulder to shoulder… [and were] superior in valour and in the great size of their shields” (Diodorus Siculus XI.7) – the only real tactic recorded being used by the Greeks at Thermopylae is the Spartan use of ‘feigned flight’, turning their back on the Persians in order to encourage them to break ranks and then turn around and fall upon them (Herodotus VII.211.3).

Another aspect of the Greek dispositions is that they “stood ordered in ranks by nation” (Herodotus VII.212.2), something reflected in 300 Spartans when Leonidas comments about men fighting better side by side with his friends. Of these many nations, in the ranks of both armies, you could question any number of costume choices for the various Greeks, Persians and other eastern peoples, but this would be expecting too much from almost any film.

Also for dramatic effect, the cinematic Xerxes exposed himself a little too much, not only at the battle, but beforehand too. In the opening scene of the Persian army crossing the Hellespont, it was a little surprising to not see the Spartan spy Agathon make a move to strike at the Persian king when he was brought mere feet before him. Similarly, at the film’s climax, Xerxes was more than in range of a Greek arrow or javelin, although at least the Spartans, under their second-in-command, Pentheus (played by Robert Brown, who also played ‘M’ in the 1980s Bond films) did make a move to try to get to him.

The film makes much of the bravery, skill and military reputation of the Spartans, which was of course on full display at the Battle of Thermopylae, but it also presents other aspects of Spartan society, with a rather good level of historical accuracy.

The film makes use of famous pieces of ‘Laconic wit’ uttered at Thermopylae. One of the ‘300’, Dienekes was recorded responding to the Persian threat that their arrows would blot out the sun by saying that it would be good to fight in the shade (Herodotus VII.226.1-2; Plutarch, Moralia 225B puts this in the mouth of Leonidas (as does the film); cf. Stobaeus, Florilegium, VII.46; Valerius Maximus, III.7, ext. 8; Cicero, Tusculan Disputations, I.42).

300 Spartans also has Leonidas tell the Persians to ‘μολὼν λαβέ’ – ‘Come and take them’ – when the Greeks are told to surrender their arms, which is a recorded statement from the Spartan king, although in the pages of Plutarch, this appears not in a conversation but in an exchange of letters between Xerxes and Leonidas (Plutarch, Moralia 225D).

A less well-known Spartan retort of unnamed source is given to Phyllon when he is ordered to go back through the lines with orders – “I came with the army, not to carry messages, but to fight” (Plutarch, Moralia 225E). The story and script writers for 300 Spartans had certainly read their Herodotus and Plutarch.

300 Spartans also presents aspects of the Spartan political constitution, including its use of a dual kingship (although Leonidas’ Eurypontid colleague, Leotychidas II, gets no lines in his very brief appearances on screen). While the film is correct to present the Spartan ephorate as being comprised of 5 men, those men should be between 30 and 60 years old i.e. the age of military service. 300 Spartans seems to have its ephors as older men, suggesting that it has somewhat combined the ephorate with the Gerousia, the 30-strong Spartan ‘council of elders’ elected from those over 60.

The film’s depiction of the ephors as something of a check on power of the kings’ is correct, although their role in looking to enforce the respecting of the Carneia festival might have them going beyond their recorded purview. That said, religious festivals are recorded as hindering Spartan participation in military actions, with the Carneia impeding Spartan involvement at the battles of Marathon and Thermopylae (Herodotus VI.106, VII.206).

Another depiction in the film that caught my eye for positive and negative reasons was that of Spartan women. I have already mentioned 300 Spartans usage of the ‘deceptive woman’ trope in the form of Artemisia, and it uses something of another trope in having Queen Gorgo and Ellas taking part in some sort of weaving or cloth-making. This was something that the ordinary Greek woman would have partaken in, but in Sparta, cloth-making and weaving were considered activities for slaves/helots, rather than Spartan women.

Despite this mistake, 300 Spartans does present some accurate depictions of Spartan women. Their independence in comparison to other Greek women is mentioned. Women are seen in the company of men; Queen Gorgo is seen taking part in some court ceremony, while Phyllon seems to be having to sneak away from his duties to meet up with Ellas.

Ellas having trouble completing the march to Thermopylae might be a little at odds with the athletic training Spartan women underwent, but then Phyllon, a fully trained Spartan, had trouble completing the march too. Furthermore, Ellas was shown as being capable of physically defending herself, taking down both Phyllon and Ephialtes.

There are so many other things that could be brought up with regards to 300 Spartans and its successes and failures of historical accuracy, but that would be to miss the point of it being a movie made for entertainment, not a documentary, and holding Rudolph Mate, George St. George, the cast and crew up to an impossible standard.

As it is, the scriptwriters have clearly gone to some lengths to reflect events and even speech that are recorded in historical sources such Herodotus, Diodorus Siculus, Plutarch and others (even if that means leaning on some of said record’s exaggerations).

The Battle of Thermopylae has been celebrated since antiquity as an example of bravery, patriotism, sacrifice, and heroic persistence against seemingly impossible odds, and Rudolph Mate’s 1962 rendition, 300 Spartans, is a more than adequate retelling of that story.

Peter Crawford and Katerina Kolotourou