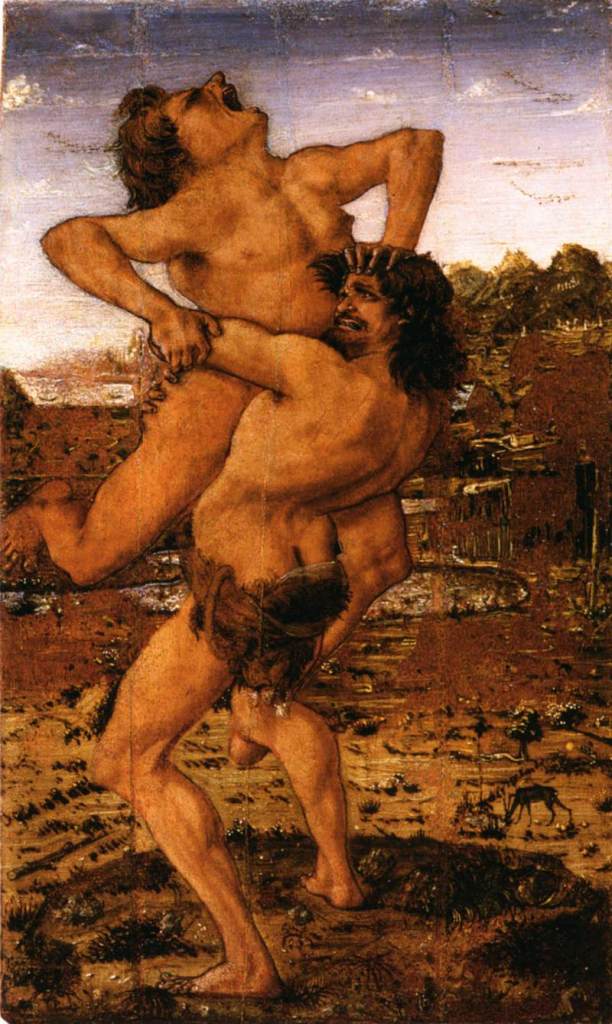

Latest Event Updates

Almost Up-setting the Order: The Kharijite Statelets of the Second Fitna (ii) The Najdat

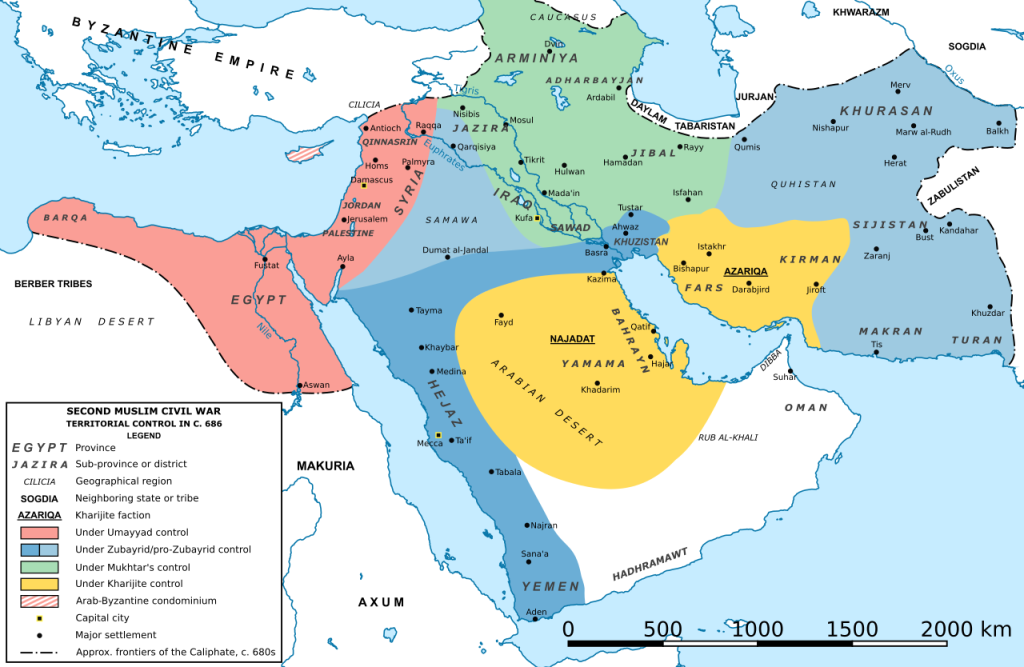

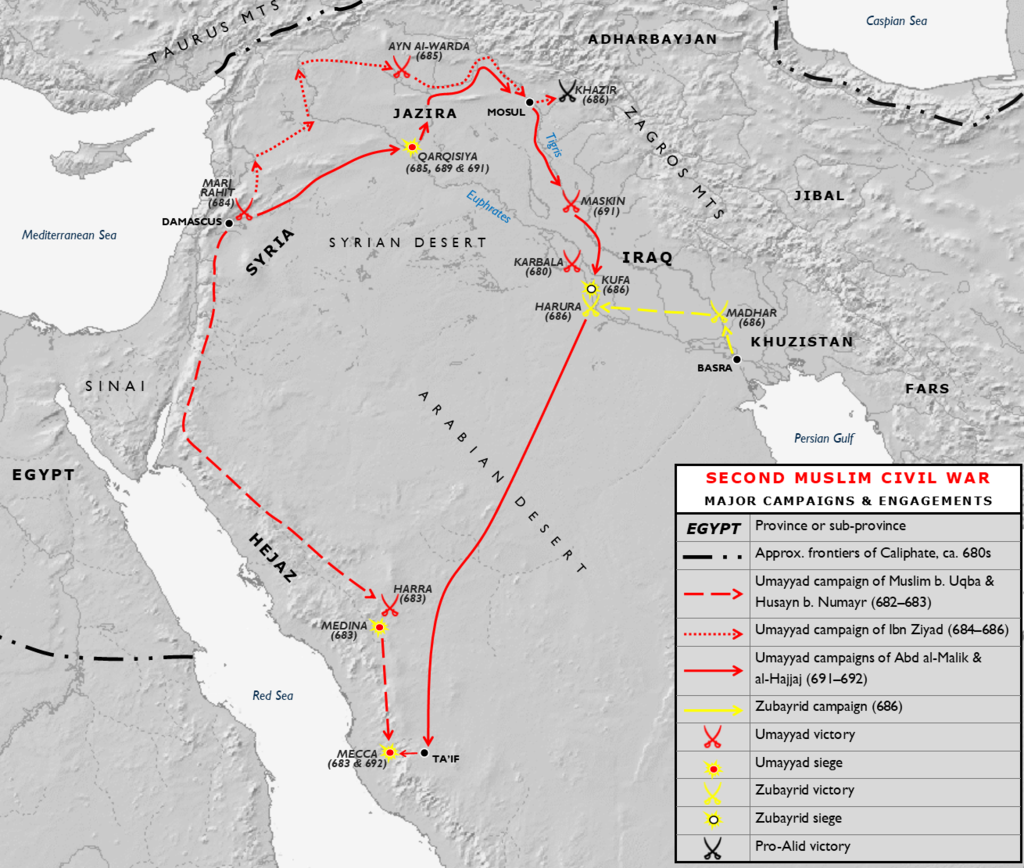

The doctrinal divide that sealed the fate of Qatari’s burgeoning Azariqa statelet in Kirman was not the first instance of such internal strife. When al-Azraq was driven out of Basra by the Zubayrids, not all of his followers went with him to Ahwaz. A group under Najda b. Amir al-Hanafi disagreed with al-Azraq’s leadership and moved south-west to join the Kharijites of Abu Talut in Yamama, a region from where Najda hailed.

Upon moving into Yamama, Abu Talut had established himself on a large tract of agricultural land called Jawn al-Khadarim, distributing the land and its resident slaves amongst his followers. And when Najda’s group arrived in the region it brought with them considerable loot taken from a caravan heading to Mecca from Basra. He had this look distributed amongst the Kharijites of Yamama and advised them to continue using the freed slave labour as a basis for their power in the region. Such a move proved successful and popular, to the extent that when Najda suggested that he be the leader of Kharijite Yamama, he was unanimously accepted, even by Abu Talut himself. This led to this group being called after its new leader – the Najdat.

Using his new leadership position and the solid agricultural base provided by his lands, Najda was soon on the warpath. Before 685 was out, he raided Bahrayn in eastern Arabia, winning a great victory at Dhu’l-Majaz and capturing a large amount of corn and dates that had been looted from a nearby market.

This raid was followed up a year later by the forcing of a more permanent Kharijite presence in the region. Intervening in a tribal conflict, Najda took control of the major port city of Qatif, which became one of his major headquarters. The claiming of Bahrayn was to be the first in a series of victories that would stretch the Najdat statelet to much of the Arabian Peninsula and threaten to split the Zubayrid caliphate in half. And the Zubayrids were not idle in confronting this threat. The caliph’s son and governor of Basra, Hamza, sent an army of 14,000 men to challenge the Kharijites, only for it to be ambushed by Najda and put to flight.

Najda followed up this victory by sending his lieutenant Atiyya b. al-Aswad to Oman, where he defeated its chieftains to bring the region into under Najdat control; however, this only lasted a few months as Atiyya’s deputy was defeated and ejected from the region. This defeat and Najda’s unequal distribution of reward and possible communication with Abd al-Malik, the Umayyad caliph, led to growing divide between Atiyya and Najda. This would culminate in 687 with Atiyya taking a group of supporters to Sistan, on the Iran/Pakistan frontier, where they established their own Kharijite faction – the Atawiyya.

This was only a momentary bump in the road for the Najdat, as their control over Bahrayn was tightened, another deputy marched to Hadhramawt and Najda himself led an army into Sana’a, with the capitulation of both making the entirety of Yemen tributary of the Najdat. These successes actually made Najda more powerful in Arabia than al-Zubayr, although the victory over the Alids in mid-April 687 had greatly expanded the territory that recognised al-Zubayr as caliph.

This did not perturb Najda, with Kharijite raids striking into the Hejaz. Perhaps only religious concerns over attacking the holy sites of Mecca prevented the Najdat from making more headway than they did at this point. And even with this hesitation, it did not stop Najda from blockading much of the Hejaz.

However, one thing did make into Mecca – Najda himself. In mid-687, in a true testament to the perception of Najdat power, its leader was ‘allowed’ to lead a group of his Kharijite followers on the Hajj pilgrimage. If he tried to stop him, al-Zubayr proved powerless to prevent such an incursion into what was his capital city. With this demonstration, the Najdat appeared the equal of the Zubayrids and the Umayyads.

Despite worries over using violence towards the holy sites, Najda forged on into the Hejaz after returning from his Hajj. His forces approached Medina, but when it refused to capitulate without a fight, Najda again withdrew from attacking a holy city. Instead, Najda moved against Ta’if, near Mecca. Here, he received a more open welcome, with the Ta’if leadership giving their allegiance to the Najdat. By 689, the Kharijites controlled enough of the southern Hejaz to appoint their own governor over a region taking in Ta’if, Sarat and Tabala, while also collecting tribute from even further south. Virtually all of Arabia was under Najdat control. It would seem to only be a matter of time before Najda looked to finish off the Zubayrids. And yet, this was to be the peak of Najdat power.

As al-Hajjaj arrived in the Hejaz in late 691, he may have been surprised by the lack of Zubayrid opposition, but that does not mean that there was significant Kharijite opposition instead. Bypassing Medina and Mecca due to orders from caliph Abd al-Malik not to attack the holy sites (yet), the Umayyad general moved against Ta’if, his hometown, and quickly removed whatever allegiance it owed to the Najdat.

Indeed, during these initial Umayyad moves and even their subsequent attacks on first Medina and then Mecca itself through 691 and 692, attacks brough an end to the Second Fitna upon the death of al-Zubayr in late 692, there was no mention of Kharijite resistance to the Umayyad incursion.

For a statelet at the height of its powers, it seems peculiar for the Najdat to be so inactive during the battle for the Hejaz. How had it come to be that Najda and his followers were absent from this climactic end of the second Muslim civil war?

Abd al-Malik had clearly recognised the Najdat threat as dealing with them appears to have been part of al-Hajjaj’s remit as governor of the Hejaz, Yemen and Yamama, a remit that encompassed significant lands under Najdat control. However, it appears to be Abd al-Malik’s diplomacy that undid the Najdat statelet more than the military actions of al-Hajjaj or the Zubayrids.

We have already seen how contact with the Umayyad caliph had led to a schism in the Najdat with Atiyya’s departure to Sistan in 687 and it appears that a similar episode happened again in around 690. Almost certainly knowing exactly what he was doing, Abd al-Malik reached out to Najda, offering amnesty and the Yamama governorship in return for recognition of his caliphate. Najda rejected the offer, but maintained cordial relations with Damascus, with this being enough to cause dissension in the Najdat ranks.

Being a faction built on what they saw as ideological and religious purity in the face of the corruption of Islam, this Kharijite dissension quickly turned into a full split between those supposedly open to negotiations with the ‘usurper’ Abd al-Malik and those hardliners who now saw Najda as irrevocably tainted ideologically and religiously. It is likely that there was more at play than just dissent at Umayyad dealings – there was dispute over the dissemination of pay to certain parts of Najdat military, while Najda reputedly gave preferential treatment to his close associates despite reports of their religious impropriety.

This split redirected Najdat attention and then drained away Najdat power at a time when a potential victory was in the offing. It is not beyond the realms of possibility that opposition to the Umayyads amongst Zubayrid supporters could have seen Najda’s ranks swollen to an extent when they could have challenged the forces of al-Hajjaj.

As it was, instead, the cunning diplomacy of Abd al-Malik had not only neutralised the Najdat but ultimately destroyed it. Even before the final defeat of al-Zubayr in Mecca, Najda had been murdered by Najdat radicals under Abu Fudayk in Bahrayn.

It was quickly proven how much the Najdat statelet had relied on Najda’s leadership abilities and reputation. Abu Fudayk tried to take up the mantle of Najdat ‘commander of the faithful’ and was initially successful in repelling an Umayyad invasion from Basra in 692; however, this was only delaying the inevitable. The following year, a combined army of Basran and Kufan forces defeated Abu Fudayk at Mushahhar, just south of Qatif, before capturing the last major Najdat holdout by the end of the year. The Najdat Kharijites themselves did not completely disappear, surviving in some form for another two centuries or more, but they were never the same coherent threat they had been under their eponymous leader.

Given the solidity and indeed power it had managed to accrue under the leadership of Najda, it is somewhat surprising that the Najdat collapsed before its much less secure sister statelet in the Azariqa. But only somewhat. It can never be surprising that a faction whose identity was formed through an extreme even fanatical conformity to religious practice and tradition sees its leadership, no matter how successful, or even the very faction itself overthrown by the necessity of adherence to an impossibly strict code of conduct and belief.

The Kharijites as a whole survived the Umayyad destruction of the Najdat and the Azriqa in the 690s, but they were significantly weakened. There would be a significant Kharijite rebellion across the caliphate in the 740s and 750s, although the leading roles was taken by more moderate Kharijite groups – the Sufriyya and Ibadiyya, with the more militant groups gradually eliminated by the Abbasid caliphate. These moderate groups would have some ephemeral success in the caliphal heartlands, capturing major centres like Kufa, Mosul and even Medina and Mecca for a time, only to be ejected; however, they both saw more lasting success on the fringes of the caliphate – a Sufriyya dynasty ruled Morocco for 150 years from 750, while the Ibadiyya enjoyed similar success at around the same time ruling Algeria and Oman, with the modern population of the latter made of a majority of Ibadi Muslims.

While modern day Ibadi in Oman and North Africa (where they absorbed their Sufriyya brethren by the 11th century) are ultimately the descendants of moderate Kharijites, they strongly condemn the extremism and violence of Kharijites such as the Najdat and Azariqa, even though those groups came close to upsetting the established caliphal order during the Second Fitna.

Bibliography

Dixon, A.A. The Umayyad Caliphate, 65–86/684–705: (A Political Study). London (1971)

Gaiser, A. Muslims, Scholars, Soldiers: The Origin and Elaboration of the Ibadi Imamate Traditions. Oxford (2010).

Hagemann, H-L. The Kharijites in Early Islamic Historical Tradition: Heroes and Villains. Edinburgh (2021).

Watt, W.M. ‘Khārijite thought in the Umayyad Period,’ Der Islam 36 (1961) 215–231

“What a [Herculean] Manoeuvre!”: Inventing the Bear Hug

What do the following men all have in common?

- Superstar Billy Graham

- Ted Arcidi

- Tony Atlas

- Mark Henry

- Bill Kazmaier

- Brock Lesnar

- The Yeti

- Bruno Sammartino

- Georg Hackenschmidt

Aside from all being professional wrestlers, they also all used the bearhug as a ‘finishing’ move at some point in their careers.*

And yet, while the lattermost of that list – Georg Hackenschmidt – is usually credited with creating the professional wrestling version of the bearhug, the hold itself is much older than the earliest years of the 20th century.

Its invention ‘dates’ back to mythological times, or at least to the period when these myths were being formulated or written down in the mid-1st millennium BC. Furthermore, the ‘first’ bear hug came during one of the most famous Greek myths: that series of intentionally (but not actually) impossible tasks given by Eurystheus, king of Tiryns – the Twelve Labours of Hercules.

During his fulfilling of the 11th Labour – stealing apples from the garden of the Hesperides, Hercules has his brush with wrestling history. While searching for the garden in the Libyan desert of North Africa (Apollodorus 2.5.11; Diodorus 4.17.4), Hercules met a certain Antaeus, a giant son of Poseidon and Gaia.

The mythological nature of Antaeus and how he is identified solely by his mythological actions towards various opponents and possibly the Herculio-centric nature of the story-telling may be reflected in his name stemming from the Greek ἀντάω meaning ‘I oppose’, Ἀνταῖος means ‘opponent’. Antaeus also appears in Berber/ Amazigh mythology as ‘Anti’, and with his wife, the goddess Tinge, father the daughters Alceis/Barce and Iphinoe.

True to his name, Antaeus would challenge all passers-by to a wrestling match, which would have been quite the test due to him being a giant demigod who was skilled in wrestling (Diodorus Siculus 4.17.4); however, Antaeus had an extra secret weapon in his blood. While he received significant strength from Poseidon, it was his mother Gaia from whom he gained an unfair advantage over his opponents: so long as he remained in contact with the ground – i.e. Gaia herself – Antaeus could replenish his “enormous strength” (Lucan, Pharsalia 4.600).

And as Archaic Greek wrestling typically involved attempting to force your opponent to the ground and pin them, Antaeus’ ability to gain strength from contact with the ground made him almost unbeatable, for if his sheer size and wrestling skill were not enough for victory, he could simply outlast his opponents. Due to this combination of enormous strength, colossal skill and unending stamina, it was even claimed that he would have been a significant threat to the gods themselves (Lucan, Pharsalia 4.597).

If such an unfair advantage was not bad enough, Antaeus killed those he defeated (everyone) and used their skulls in the construction of a temple to his father, seemingly for the roof (Pindar, Isthmian Odes 1.4.52-54).

Given the opening question of this piece, some of you may already be recognising how Antaeus is going to be bested, but even with such a ‘plan’ in mind, it would require someone of significant wrestling skill and immense strength to achieve it – unfortunately for Antaeus, someone of just such a skill set had found himself walking through the area of the Libyan desert where Antaeus offered his challenges. He might not have been as big as Antaeus, but Hercules was every bit as strong and more (cf. Tzetzes, Chiliades 2.364-365).

In terms of detail of the Antaeus/Hercules contest, it is Lucan’s Pharsalia (4.660-739) that provides the most in-depth account, while most others merely present the location and the outcome. Of course, the lack of other material giving depth to the contest suggests that Lucan has invented much of what he writes, even if he puts the telling of the story in the mouth of an African local speaking to Gaius Scribonius Curio during the Caesarian civil war of the early 40s BC. Even then, Lucan’s retelling is not all that long, but there is just enough to divide it into four small sections – the prelude and then three ‘rounds’.

Prelude and Preparations

Rather than present the contest as an incidental sideshow surrounding Hercules’ 11th Labour, Lucan presents it more as the ‘Mighty’ Hercules travelling to Libya specifically to deal with Antaeus, who was more of a monstrous/ogre-like menace to passers-by and innocent Libyan farmers.

Both men three off their coverings – Hercules the skin and mantle of the Nemean Lion (his first Labour) and Antaeus a hide of local beasts (Lucan, Pharsalia 4.683-686) – as Greek wrestling contests were fought naked.

Lucan also intimates that Antaeus had never had much need to use his energy replenishment special move due to the inability of his opponents to knock him down at all. However, in his bodily preparation for the contest, Antaeus could betray some wariness of Hercules. While Hercules rub oil onto his limbs as was the norm for a wrestling contest, Antaeus covered his body in sand to have more contact with the ground than just the soles of his feet. That said, this could be something that Antaeus did before all of his contests, rather than just for that with Hercules. Whichever it was, one might suggest that it was a ‘heelish’ tactic to gain a further advantage over his opponent, although a wrestler rubbing dirt into his hands was a way to increase grip.

Round 1

The first part of the contest began with locked arms, with both trying “to secure a neck-hold.” Both were surprised by their failure to immediately gain the upper hand and by the strength of their opponent. In response, Hercules settled into a strategy of wearing Antaeus down, which would have been a good move against virtually any other opponent…

Initially, it seemed to work, with Hercules’ strength able to make Antaeus “pant and sweat” to the point that he lost his form, allowing Hercules to unbalance him with a strike to the upper leg and then transition into a waist lock, kick his legs out from under him and slam Antaeus into the ground.

This may well have resulted in victory for Hercules, and was probably the kind of move that had won him matches in the past, but Antaeus had his Gaia-given power.

The combination of the sand he had covered himself with and the contact with the ground saw

“fresh blood coursed through his veins, his muscles bulged, his body regained strength.” Much to Hercules’ shock, this rejuvenation allowed Antaeus to escape his grasp and re-establish his vertical base.

Lucan even suggests that Antaeus’ escape left Hercules feeling even more apprehensive than then he had fought the hundred-headed Hydra… much to his step-mother Hera’ delight!

Round 2

The second ‘round’ of the fight saw a similar battle of strength. Hercules, “exhaustion overcoming him and making the sweat start from his neck”, had not had to struggle this much before, even when he briefly held up the heaves for Atlas the Titan.

Despite Hercules’ struggles, it was again Antaeus who began to weary, but this time he did not wait until Hercules was able to take him down. Instead, he deliberately threw himself to the ground, drinking deeply of the replenishing energy Mother Earth provided for him. “One might say that she herself felt worn out by the strain of this wrestling match.”

However, it seems that Antaeus had made what he was doing all too obvious. Hercules therefore changed his strategy – rather than try to force Antaeus to ground, Hercules determined to keep him upright, or failing that, to make sure if he fell, that he fell on top of Hercules.

Round 3

With this change in strategy, the third ‘round’ proved decisive in this heaviest-weight contest.

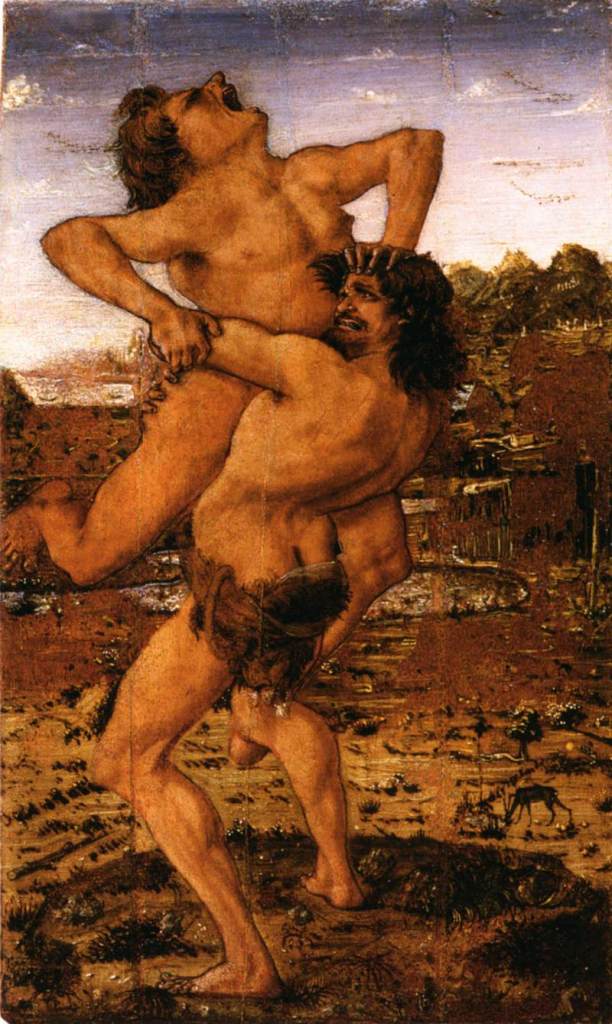

When they engaged once more or perhaps grabbing him whilst he lay on the ground the second time, Hercules lifted Antaeus off the ground. He then “resisted his frantic efforts to cast himself down,” all the while squeezing Antaeus in a what would technically be called an elevated bear hug, although it is not explained whether it was a rear or frontal bear hug.

This lack of clarity is demonstrated in the various depictions of the Herculean bear hug, with there being no settled style – both frontal and rear bear hugs are depicted.

Frontal bear hug

Hercules slaying Antaeus, painting by Florentine artist Antonio del Pollaiuolo in c.1460, now in the Uffizi gallery, Florence.

Hercules Fighting Antaeus in the Hofburg Quarters, Vienna

18th century French sculpture in the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore

17th century Italian bronze in the Metropolitan Museum, New York

Rear bear hug

Roman sculpture of Hercules and Antaeus in the Uffizi collection in Florence

In his 1634 work Hercules Fighting Antaeus, Spanish painter Francisco de Zurbarán portrays it as a rear bear hug – i.e. Hercules has lifted Antaeus from behind.

19th century bronze in the Metropolitan Museum, New York

How ever Hercules held him aloft, the separation from the ground and the squeezing strength of the Heruclean bear hug eventually took their toll on Antaeus. While exact details are not given, it is safe to assume that Hercules squeezed the life out of Antaeus, likely breaking his back in the process; however, even as “he felt the giant’s body stiffening… [Hercules] continued to hold it aloft, and thus prevented Mother Earth from reviving her dying son” (Lucan, Pharsalia 4.735-736; cf. Hyginus, Fabulae 31; Apollodorus 2.5; Diodorus Siculus 4.18.1, 27.3).

“There withal was wrought Antaeus’ brawny strength, who challenged him to wrestling-strife; he in those sinewy arms raised high above the earth, was crushed to death”

Quintus Smyrnaeus 6.318-323

It was only long after the “chill of death” had taken Antaeus that Hercules felt safe to release his bear hug and rest Antaeus’ body back into the bosom of his mother (one would think that a referee would have stopped a fight a good bit before that and possibly even disqualified Hercules for refusing to release the hold…).

Not only did Hercules take Antaeus’ life, some Berber/Amazigh traditions have him taking his wife as well. The liaison between Tinge and Hercules led to the birth of Sufax, the legendary founder of the city of Tingis (modern Tangier in Morocco), who named it after his mother (Livy 30.12; Plutarch, Sertorius 9.4), although Plutarch says that this lineage of Sufax was likely created to satisfy Juba II of Mauretania, who claimed descent from him (Plutarch, Sertorius 9.5).

There is also a tradition that it was Iphinoe, daughter of Antaeus and Tinge, that became a consort of Hercules, resulting in the birth of Palaemon, although his mother is also recorded as being Autonoe, daughter of Peireus (Tzetzes, Lycophron 663; Apollodorus 2.7.8).

As to the fate of Antaeus’ remains, during his African campaign, from which we get the report in Lican of a more in-depth contest between Antaeus and Hercules, Curio “marched up to a rocky hill, pitted with caves, traditionally known as the ‘Tomb of Antaeus’” (Lucan, Pharsalia 4.589-590). However, somewhat at odds with this is how the Roman general, Quintus Sertorius, in 81 BC, was told by the people of Tingis that the vast remains of the giant Antaeus could be seen in a burial mound in the Libyan desert. Finding the mound, Sertorius had the massive bones exhumed and “was dumbfounded, and after performing a sacrifice filled up the tomb again, and joined in magnifying its traditions and honours” (Plutarch, Sertorius 9.4).

Tingis is quite removed from the area that Curio had been campaigning in 49BC – about 1,500 miles removed in fact – so it is unlikely, if not impossible, that Sertorius and Curio visited the same site. Certainly, Sertorius seems to have only campaigned in Mauretania, modern Morocco, while Curio was seemingly only in what is now Tunisia.

More than one place claiming to be the burial site of the vanquished Antaeus likely demonstrates the mythological nature of the story; however, it also highlights the spread of that story geographically and culturally, as it stretched across North Africa and between Greek and Amazigh/Berber cultures.

This spread of the story took with it the supposed invention of the elevated bear hug and some of the technique involved in its use. But one thing that the spread of this story could not impart on those who wished to replicate Hercules’ match-winning manoeuvre was the supposed strength of those involved in its invention.

While in no way denigrating the feats of strength and athleticism achieved by the men listed in the question at the beginning of this piece, none of them could emulate the power scale of two demigods – one the son of Zeus, the other the son of Poseidon and Gaia. That first bear hug was almost certainly to be the most powerful to ever be seen.

* For you pro wrestling aficionados out there, it is somewhat surprising, particularly given its supposed mythological inventor, that the ‘Mighty’ Hercules Hernandez did not use the bear hug as a signature move during his career, aside from seemingly a brief period in 1984-1985 when he was performing as ‘Mr. Wrestling II/III’ in Mid-South Wrestling.

Other than Odysseus: Survivors of the Odyssey

Odysseus: We now set out on our odyssey.

Crewman: [raising hand] what’s an ‘odyssey’?

Odysseus: A long journey named after the only survivor.

Crewman: Oh ok… wait… what?!?

An amusing joke for a classicist, which assumes knowledge of the ‘fact’ that Odysseus was the only survivor of his ill-fated attempt to return home to Ithaca after the Trojan War. However, in the course of the second great journey to a homeland after the Fall of Troy recounted in the Aeneid, we find that at least two of Odysseus’ crewman had survived the various encounters with gods and monsters to meet up with the emigrating Aeneas and his crew. It must be said that neither of the names given for these two survivors appear in the Iliad or the Odyssey, which makes it likely that they are later interpolations invented by the Romans to make further connections between the works of Homer and their own burgeoning origin myth.

Achaemenides of Ithaca

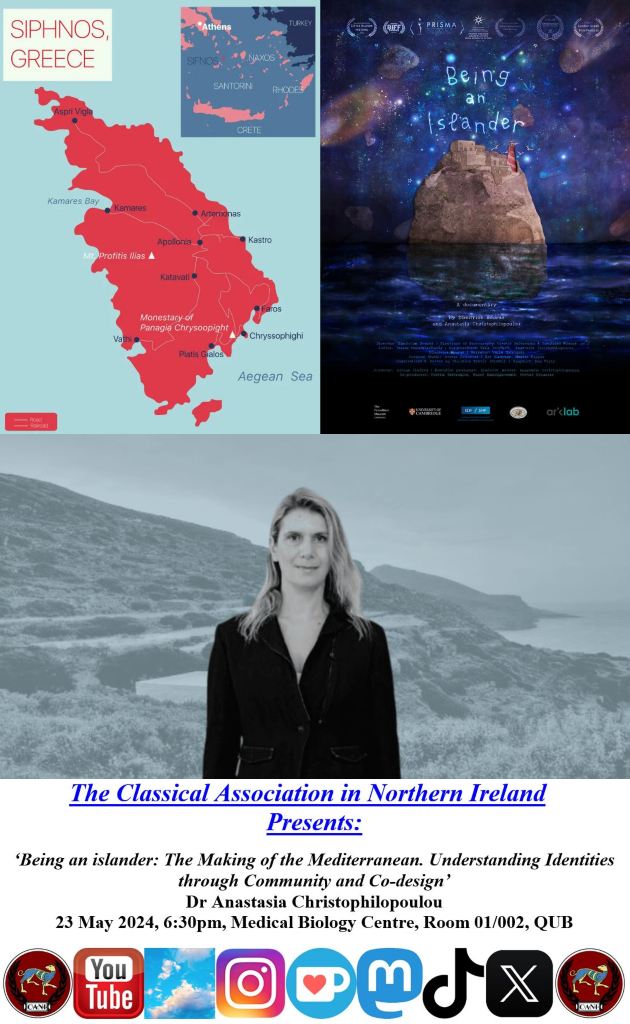

The first supposed survivor of the ‘Odyssey’ was met by Aeneas and his followers on the island of cyclopes (Virgil, Aeneid 3.591ff; Ovid, Metamorphoses 14.158ff). As they surveyed the shore, a man “in pitiable plight and half-dead with hunger” with a straggling beard, rags held together with thorns and covered in filth emerged from the woods.

They recognised him as a Greek and he recognised them as Trojans, which gave him the briefest moment of pause, only for his desperation to overcome any fear of the enemy. He begs Aeneas and his men to take him from the island, even if it is to execute him as a Greek enemy, such is the terror and hardship he has endured.Aeneas and his followers urged the man to tell them his name, origin and what he was so scared of, but it was only when Aeneas’ father Anchises offered the man his hand, that he had the courage to reveal his story.

“My native land is Ithaca. I am a comrade of the unfortunate [Odysseus]. My name is Achaemenides. My father Adamastus being poor, I went to Troy – cursed be the day!”

He retells the story of their meeting with the cyclops and the horrors of seeing two of this shipmates killed and eaten by Polyphemos, and then that he had been left behind during the escape. Achaemenides does not explain why he was left behind in the cave – did it require an extra pair of hands to get a man attached to the bottom of a sheep in order to escape Polyphemos’ attention at the entrance of the cave, with Achaemenides therefore the odd man out at the end?

Perhaps the plan had always been for one man to be left in the cave, with those who escaped then making enough noise to attract Polyphemos away from the cave entrance, allowing the last man – chose by lot or volunteering – to then escape. This is what came to pass, only for Achaemenides to be left behind as panic overtook the other escapees and/or, even when blinded, Polyphemos proved still a threat to the Greek crews and their ships.

In the pages of Ovid’s Metamorphososes, Achaemenides explains that he could not cry out to the escaping ships as that would reveal his presence to Polyphemos and the other cyclopes. He could only watch as Polyphemos hurled rocks at Odysseus’s ships, leaving him stranded on the island in constant fear for his life should any of the wild animals or the cyclopes find him.

In terms of how long he had been stranded there, Achaemenides states that he had seen the ‘horns of the moon’ – a crescent moon – three times, suggesting that he had been stranded on the island for at least 5 weeks, if not much more – to see the same version of the ‘horns of the moon’ could take a month at a time. Achaemenides may have been having to eke out a miserable and terrifying existence for over three months.

Any wonder then that he was so happy to see Aeneas and his Trojans making landfall. Even less wonder that he immediately warned his rescuers that they needed to leave. And sure enough, the monstrous Polyphemos appeared lumbering down the mountainside to the shore, using a pine tree to guide him to the sea, where he attempted to wash his wounded eye. The cyclops heard the clamouring of the Trojan escape and chased after them in vain, with his screams bringing down the other cyclopes to see Aeneas’ ships leaving with Achaemenides onboard.

We might ask why Virgil or the Romans in general would invent the character of Achaemenides. It provides a direct connection between the Aeneid and the Odyssey from the Greek side of things and allows Virgil to show how magnanimous Aeneas could be in saving a member of Odysseus’s crew, and bearing little grudge over the destruction of Troy. And in return for this magnanimity, Achaemenides not only gives his loyalty to his Trojan rescuers and immediately exhorts them to flee the island, he is also able to serve as a useful source of knowledge for Aeneas going around the islands and shores he had already visited.

Macareus of Neritus

The second survivor of the Odyssey other than Odysseus is spoke of in Ovid’s Metamorphoses. It has it that this second survivorwas found by Aeneas’ expedition after it emerged from the Stygian realms near the Euboean colony at Cumae. Arriving on the shore that he would name after his nurse, Caieta – that is the Bay of Gaeta, Aeneas discovered another “Greek had found a home” there. This was Macareus, originally from the town of Neritus on mainland Acarnania in western Greece.nMacareus immediately recognises Achaemenides, shocked to find him still alive…

“what chance or what god saved you, Achaemenides? Why does ship belonging to the barbarous Trojans carry a Greek on board?”

Once he describes his ordeal with the cyclops and explains how he owes the Trojans his unending gratitude due to their saving him from the island, Achaemenides then enquires about Macareus’ travels after the escape from the cyclopes.

Macareus recounts how Odysseus’ received the winds of Aeolous, which after 9 days brought then fleet within sight of Ithaca, only for the jealous crew to open the bag they were contained in thinking that Odysseus was concealing gold from them. This saw the ships carried all the way back to the harbour of Aeolus. At their next stop, Macareus was chosen along with two other crewmates to treat with Antiphates, king of the Laestrygonians, only for one of his comrades to be eaten by the cannibal ruler. The other crewman and Macareus escaped back to Odysseus’ ship, but it was only one to survive the encounter with the Laestrygonians, with the other ships destroyed and their crews either drowned or eaten…

This single ship then makes landfall at an island off the coast of Rome called Aeaea, which could supposedly be seen from the Bay of Gaeta as Macareus points to it in his retelling (it is a mythical island). Macareus warns the Trojans to stay away from there as it is the island of Circe…

Macareus tells of how he was again chosen by lot, along with 21 others to make contact with the inhabitants of the island. They were welcomed with a banquet by Circe, who gave them a concoction that turned them all, bar one, into pigs (this transformation and another story of Circe’s powers is why Ovid recounts the survival of Macareus).

“… my body began to bristle with stiff hairs, and I was no longer able to speak, but uttered harsh grunts instead of words. My body bent forward and down, until my face looked straight at the ground, and I felt my mouth hardening into a turned up snout, my neck swelling with muscles. My hands… now left prints like feet upon the ground.”

Macareus and his pig brethren were shut up in a pigsty and were only saved due to one of their original number, Eurylochus, having refused to drink the concoction. He escaped to inform Odysseus, who protects himself from Circe’s magic by taking moly. Surviving his own drinking of the concoction untransformed, Odysseus persuades Circe to turn his men back. The crew then spent a year living on Aeaea, where Macareus hears may stories of the power of Circe, including that of Picus and Glaucus.

When the crew finally departed Aeaea, Circe “told us of the dangerous voyagings, the long, long journey and perils of the cruel sea” they were still to face, which thoroughly frightened Macareus, who jumped ship when it reached the Bay of Gaeta, where he decided to remain. This decision saved his life. Had he stayed onboard, Macareus would have been fated to die at the hands of Scylla or in the shipwreck caused by Zeus in retaliation for the crew’s hunting of Helios’ sacred cattle on the island of Thrinacia; it was this shipwreck that saw Odysseus become the ‘sole survivor’ of the Odyssey.

Both Achaemenides and Macareus are used as storytellers in the Aeneid and Metamorphoses. Ovid, in particular, in having Achaemenides and Macareus meet, demonstrates how history has been passed down orally, becoming a coherent story in the process before being committed to writing. The lack of mention of these men in the Odyssey suggests that they were made up almost expressly for this purpose, taking advantage of there being so many crewmates on Odysseus’ voyage who are not named.

If such a story-telling device was to be used today, it would be considered ‘fanfiction’ and/or extrapolating of a story that did not need to be told from minutiae or unimportant gaps in a larger story. For Virgil, it was a way of further anchoring his much later addition into the story of the Homeric cycle.

Before the Romans Got Hold of Him: Aeneas in the Iliad

You might see people opining that the story of say the Star Wars movie Rogue One is built upon a question that no one really needed answering – why has an exhaust port connected to vital systems of the Death Star been left unshielded? You might also think that latching on to such minutiae, minor characters or embellishing an established story was the preserve of modern Hollywood film studios or fanfiction produced by people who just want more from their favourite stories and characters; however, it is a much older and well-established literary idea than you might think. Some of the most famous writers and stories are just such embellishments and ‘fanfiction.’

William Shakespeare put words in Mark Antony’s mouth for the ‘Friends, Romans, countrymen’ funeral oration he gave for Julius Caesar; different words than recorded by the likes of Appian, BC II.144-147, who may even have had a report of what was said in 44BC. When it came to speeches given before or during the Peloponnesian War, Thucydides admitted to making “the speakers say what was in my opinion demanded of them by the various occasions, of course adhering as closely as possible to the general sense of what they really said.” (Thucydides I.22.1)

Even the Iliad itself is a poetic retelling of a (seemingly) historical event embellished with fantasy elements and loans from other older works and myths such as the Epic of Gilgamesh. If I were being mean, I would say that a modern equivalent for the Iliad in terms of genre fiddling is the movie 300, which took the historical setting of the Persian invasion of Greece and the Battle of Thermopylae and added various fantastical elements such as monsters and seemingly divine beings… It could even be argued that the Odyssey is merely a spin-off of the Iliad, latching on to one specific character in Odysseus and telling a story of his attempts to return home on the background of the Trojan War.

And the same can be said of Virgil’s Aeneid, which does something similar thing, rehashing/remaking the genre outlines of the Iliad and the Odyssey, only with a more minor and “fairly vague” (Williams (1985), 28) character. And yet, the Romans had created an entire mythos on the foundation of their city around this “fairly vague” character centuries before Virgil composed the Aeneid, possibly replicating how Greek colonists created connections between their new homes and the mythology of the Aegean world (Kinsey (2012) 18).

So what does the Iliad tell us about Aeneas that would make him a viable and attractive candidate for the Romans to build a foundation myth around?

Beyond his personal survival of the Trojan War, the most attractive thing about Aeneas as a link back to the ‘old world’ of the Aegean was his genealogy. He was a member of the Trojan royal family, specifically its offshoot branch that ruled the city/area of Dardania, the troops of whom he commanded during the Trojan War for his grandfather, Capys, then ruler of Dardania.

In terms of his place in the Trojan royal family, Aeneas was connected to King Priam in two ways. Through his grandmother, Themiste, who was a (half-)aunt of the Trojan king, Aeneas was a first cousin once removed of Priam (Themiste having married Capys, despite them being first cousins). Through his patriarchal line – Anchises > Capys > Assaracus, he was also a second cousin once removed of Priam, with Assaracus being a brother of Priam’s grandfather. This made Aeneas both a second and third cousin of Priam’s children, including Creusa, who would be Aeneas’ first wife.

However, even more useful for the Romans in terms of legitimacy and prestige was the identity of Aeneas’ mother. Whilst tending his herd of cattle on Mount Ida, Anchises was seduced (on the meddling of Zeus) by the goddess Aphrodite (Illiad 2.819 cf. 5.247, 5.313), who then gave birth to Aeneas. The Julians would claim divine descent from Venus/Aphrodite through Aeneas’ son, Ascanius, whom they identified with Iulus, the mythical ancestor of the entire clan. Another version has Iulus be the son of Aeneas and Creusa, while Ascanius was Aeneas’ son by Lavinia.

This divine heritage would prove of considerable help to Aeneas during the Trojan War, as his position within the Trojan royal family and captain of Dardanian forces saw him serve as a prominent lieutenant to his cousin, Hector. This in turn saw him play an active role in the fighting and shows himself to be a brave and skilled warrior and leader.

He is recorded slaying several named men – Crethon and Orsilochus, sons of Diocles, Aphareus, son of Caletor, Medon and Iasus and Leocritus, son of Arisbas (Iliad 5.541, 13.541, 13.541, 17.343). Some prominent Greeks thought twice about fighting Aeneas alone – the Trojan prince challenged Menelaus, but had to withdraw when the Spartan king brought back up (Iliad 5.541), a lesson that Aeneas seemingly learned for when he later challenged Idomenus, the Trojan brought his own back in case the Greek replicated Menelaus, which he did, leading to a group fight rather than a duel (Iliad 13.500). In Books 6 and 11, he is seen in prominent leadership roles, charged by Helenus (another son of Priam) with organising the defence of Troy, alongside Hector, and then assaulting the walls of the Greek camp. Aeneas also rallied the Trojans when they were in trouble during the fighting over the corpse of Patroclus (Iliad 17.323).

His achievements saw Aeneas “honoured by the people like a god” (Iliad 11.58). This also might seem like a comment on his divine heritage, but then Aphrodite being his mother was supposed to be a secret (Anchises was struck by lightning from Zeus for bragging about his divine liaison). Furthermore, others in the Iliad are described with similar words, although this would seem to present “honoured by the people like a god” as a known demonstrating a form of respect.

It could be that Aeneas was not above holding himself in high regard. He claimed to be as good as Hector (Iliad 5.467; cf. 6.78), and in Book 16, he shows shock and anger when Meriones luckily avoids being killed by his spear throw. Aeneas’ self-confidence even went as far as to display annoyance at Priam for not honouring him sufficiently, despite his ability and skills (Iliad 13.460). It can only be speculated as to what was at the heart of this annoyance with Priam as Homer does not go into any detail. Might the Trojan king have been put out by the love showed by the Trojans to this Dardanian captain, over and above his own children, except Hector?

While he did fight and defeat several individuals, it could be that Aeneas was brave and confident beyond his actual martial ability. The likes of Idomenus and Menelaus might have been wary of Aeneas’ prowess, but it came to the next level of fighters, Aeneas was found somewhat wanting.

When he squared up to Diomedes alongside Pandarus, not only was his colleague killed, but Aeneas lost his great horses (descended from the immortal steads of Zeus), fails to defeat the now unarmed Diomedes and is then severely wounded by his opponent throwing a huge stone at his hip (Iliad 5.225).

And yet, while he had failed to make much impression against perhaps the second best warrior of the Greeks, Aeneas allowed himself to be talked into squaring up to the Greeks’ greatest warrior, the rampaging Achilles.

To be fair, it was Apollo who encouraged this challenging of Achilles, and Aeneas was initially inclined to not listen due to recognising his own limits in the face of the skill of Achilles; however, Apollo points out that Aeneas is the son of Aphrodite, while Achilles is only the son of a nymph and will therefore be protected in the duel.

After an exchange of threats and insults, during which Achilles reveals that the two have fought before, hitherto unmentioned, that Aeneas had been lucky to survive, and that the Trojan was only taking up this gauntlet again for the potential glory to increase his chances of ruling Troy (Iliad 20.84-109).

When the duel begins, it is a quick affair. Aeneas strikes first, his thrown spear finding its mark, only for it to rebound harmlessly off Achilles’ armour made by Hephaestus. Achilles’ first strike knocks Aeneas’ shield from his hands.

Unarmed, Aeneas looks to lift a large stone to defend himself, but the sword-wielding, swift-footed Achilles is going to strike the fatal blow… and then… nothing. Aeneas was not struck down. Instead, he was whisked away from danger by divine intervention.

This was not the first time the gods had deigned to save Aeneas – he had only survived his duel with Diomedes due to first Aphrodite and then Apollo (Iliad 5.225; cf. 5.344). This would have been enough to suggest that Aeneas and anyone descended from him was divinely protected, but the climax of the (second) duel with Achilles will have removed all doubt.

Instead of Aphrodite or Apollo, it was Poseidon who saved Aeneas from Achilles (Iliad 20.291-340). This raises a significant question – whilst Aphrodite was his mother and Apollo had always viewed him as a favourite, why did Poseidon, who had sided with the Greeks throughout the war, come to Aeneas’ aid (Iliad 20.291-340)?

Even before looking for reasons given in the sources, you would be forgiven for thinking that this was only further fuel to the notion of a significant destiny surrounding Aeneas and his descendants, one that the Romans would not be slow to play up.

And when you then read Poseidon’s own reading of the situation, you can see why the Romans might have felt that Aeneas was a worthy progenitor.

“Now look you, verily have I grief for great-hearted Aeneas, who anon shall go down to the house of Hades, [295] slain by the son of Peleus, for that he listened to the bidding of Apollo that smiteth afar—fool that he was! nor will the god in any wise ward from him woeful destruction. But wherefore should he, a guiltless man, suffer woes vainly by reason of sorrows that are not his own?—whereas he ever giveth acceptable gifts to the gods that hold broad heaven. [300] Nay, come, let us head him forth from out of death, lest the son of Cronos be anywise wroth, if so be Achilles slay him; for it is ordained unto him to escape, that the race of Dardanus perish not without seed and be seen no more—of Dardanus whom the son of Cronos loved above all the children born to him [305] from mortal women. For at length hath the son of Cronos come to hate the race of Priam; and now verily shall the mighty Aeneas be king among the Trojans, and his sons’ sons that shall be born in days to come.”

Iliad 20.294-308

Not only did the god of the seas, storms and earthquakes think that Aeneas did not deserve to die for following the poor advice of Apollo in squaring up to Achilles, Poseidon almost seems to think that the line of Dardanus is not fated to be extinguished at Troy. Or at least that Zeus does not want the line of Dardanus to die out (Iliad 20.303-305).

That still does not necessarily explain why Poseidon himself needed to act to save Aeneas. If Fate was on the Dardanian prince’s side, presumably any god could have saved him, including Aphrodite (although she had proven susceptible to injury when she tried to save Aeneas from Diomedes) or Apollo. Of course, having yet another god acting in Aeneas’ favour, and one of the ‘Big Three’ no less, along with the claims of the coming glory for him and his line only makes him more attractive to the Romans.

This declaration by Poseidon on Aeneas also contains two other important characteristics of Aeneas. It highlights Aeneas’ piety – “whereas he ever giveth acceptable gifts to the gods that hold broad heaven” (Iliad 20.299), something which could be reflected in the divine aid he received on several occasions. Even his listening to Apollo’s poor advice could be seen as piety towards the gods. He also showed piety in other ways, such as his leading of the attack on Idomenus to recover the body of his dead brother-in-law and in his carrying of his injured father away from the sack of Troy. Pseudo-Apollodorus considered Aeneas to have been pious enough that “the Greeks [spared] him alone” (Ps-Apollodorus, Epit. V.21).

The second extra characteristic given to Aeneas by Poseidon is that he was “a guiltless man” (Iliad 20.297), and therefore spared the destruction of Troy, which was to be seen as the result of wrathful gods punishing offences inflicted on them by the Trojans (cf. Iliad 4.160-168, 13.622-625, 16.384-392, 21.522-524). The guilt of the Trojans might be the cheating of Poseidon, Apollo and Hercules by Priam’s father and predecessor as king, Laomedon, for services rendered to the city – the gods having built Troy’s walls and Hercules having saved Laomedon’s daughter from a sea monster (cf. Edwards (1991) 325).

Aeneas’ piety, his not being a descendent of Laomedon (great uncle/nephew through Themiste and first cousin twice removed through Capys) and the potential that the Dardanians were not tarnished by the abduction of Helen (Edwards (1991) 325) all seem to have shielded him from Trojan guilt.

This in turn seems him posited as the ‘one just man’ in the Iliad, a trope that appears in other ancient works such as Utnapishtim’s survival of the deluge in the Epic of Gilgamesh, Lot’s escaping from the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah for protecting two angels from a mob in the Book of Genesis and Baucis and Philemon escaping the flood of Phrygian Tyana for showing theoxenia towards Zeus and Hermes in Ovid’s Metamorphosis. Of course, Aeneas was not the only survivor of the Fall of Troy, with his father and son escaping the city with him and several other refugees joining up with him to form the group who would settle in Italy.

Given that he was a Trojan prince, might there have been an element of anti-Greek sentiment in the Roman choice of Aeneas as their ‘progenitor’? The opponents of the Roman state in the 4th/3rd centuries BC included the Greek city-states of Magna Graecia, that is southern Italy and Sicily. Claiming descent from one of the oldest Greek enemies in Troy differentiated the Romans more from the Greeks who had had such an influence on their actual origins and culture.

Certainly, if the Romans had wanted to pick a Greek survivor of the Trojan War, they had plenty to choose from. For example, Diomedes not only took part in the successful sacking of Troy, emerging from the Trojan Horse, he was favoured enough by the gods for his nostoi turn home to Argos to only take 4 days. He then emigrated to Italy, where he became the founder of many towns and cities, including Beneventum and Brundisium. Surely, he would be a suitable candidate should the Romans have wanted a Greek ancestor. Indeed, Diomedes appears in the Aeneid – called “the bravest of the Greeks” (Aeneid 1.96) by Aeneas – as a potential ally of Turnus against Aeneas, only for the former Argive king to state that he had fought enough Trojans and encourage the Rutulian king to make peace with Aeneas (Aeneid 11.282-284).

To sum up then, whilst Aeneas might not appear in the Iliad as much as we might think given that he receives a Roman spin-off, he receives enough attention to present a multi-faceted character with numerous attributes that would be found attractive to a people searching for a progenitor.

He was (1) royal, both among the Dardanians and a scion of the Trojan royal family; he was (2) a skilled warrior, capable of defeating or at least worrying some of the best amongst the Greeks; he was also (3) brave enough to show a willingness to take on men he had little chance of beating; more than once he is shown to be a (4) leader of men; his (5) piety towards his family and the gods, along with his origins, fed into his being (6) guiltless and just; his origins were not only royal, they were (7) divine through his mother, Aphrodite, and Poseidon posited that he was in some way protected by (8) destiny/Fate. And most importantly for his usefulness as a connection between the archaic Aegean to ancient Italy, Aeneas was (9) a survivor of the Trojan War through a combination of all of the above traits.

Bibliography

Edwards, M.W. Homer: Poet of the Iliad. Baltimore and London (1990).

Edwards, M.W. The Iliad: A Commentary Volume 5: Books 17-20. Cambridge (1991)

Kinsey, B. Heroes and Heroines of Greece and Rome. New York (2012).

Louden, B. ‘Aeneas in the Iliad: The One Just Man’ El Paso (2006) https://camws.org/meeting/2006/abstracts/louden.html

Nagy, G. The Best of the Achaeans. Concepts of the Hero in Archaic Greek Poetry. Baltimore (1979)

Williams, R.D. Aeneas and the Roman Hero. London (1985)

‘Aeneas in the Trojan War’ https://www.romaoptima.com/roman-empire/aeneas-in-the-trojan-war/

‘A Roman Presence in Ireland – the Example of the Coleraine Hoard’ – Peter Crawford

Dr Crawford considers the significance of the Coleraine Hoard, a collection of Roman silver coins, ingots and hacksilver pieces found in Antrim.

“The old, overworked statement that, ‘The Romans never came to Ireland’ no longer represents a widely-held view. If the Irish could raid and trade in Britain, then the Romans could, and did, cross to Ireland. Archaeological finds, including a silver hoard unearthed by a farm labourer near Coleraine in 1854, have taken the discussion of Romano-Irish relations beyond just “trade and raid” into a consideration of more intricate and sophisticated social and political interactions. These include army recruitment, the movement of migrants and even Irish settlements on Roman land”.

On Friday 21 January 2024, Dr Peter Crawford gave a talk on the Coleraine Hoard and considered Roman involvement in Ancient Ireland.

Venue and Event

On a bright, clear January afternoon in the centre of Belfast, nearly a hundred people gathered in the top gallery room of the historic Linen Hall Library. They were there to hear Dr Peter Crawford of the Classical Association in Northern Ireland speak about the connections between the Irish and the Roman world. From a podium at the end of the high-ceilinged hall, Dr Crawford displayed significant artifacts, maps, and manuscripts on a large screen.

This was the second event staged as part of the new partnership between CANI and the Linen Hall Library and tickets had Sold Out a few days in advance. Library Staff provided technical equipment for the Speaker, while the CANI Team manned a table to promote Classics and Ancient History in Ireland and the UK.

The Talk: Detective Work and Description of the Find

Peter explained his interest in this subject, living in North Antrim close to where a remarkable hoard of Roman material was discovered in 1854. The Coleraine Hoard was unearthed in the townland of Ballinrees long before the development of modern archaeological methods, therefore Peter located all available accounts from nineteenth century records, including local newspaper articles and old journal reports. The find had been split-up between antiquarians, jewellers, and museums, with many pieces lost, misidentified, or moved into unknown collections. Some ‘detective work’ was therefore required to determine what exactly had been discovered and where it had ended up. Each piece was significant, because every Roman coin contains images and mint marks that can be used to date where and when it was issued. This is crucial for understanding the purpose and significance of the Coleraine Hoard.

Using this information, Peter explained what was occurring in the Roman Empire at the time when the hoard was buried (c. AD 430). This was the era of Saint Patrick, when the Western Roman Empire was disintegrating and Roman Britain was subject to repeated raids from Irish, Picts and Anglo-Saxons. So, what was the Coleraine Hoard? How did this collection of Roman silver payments reach Ireland? Peter offered several theories in answer to these questions and a video recording of the event is available online.

A Roman-Irish Connection

Dr Crawford explained the use of ingots and hacksilver by the late Roman State and military. Then he outlined the main theories for how such items could have reached Ireland. The Coleraine Hoard does not resemble the random objects seized by Irish sea-raiders (artifacts like the Murlough find of Roman rings and belt-buckles – Dundrum Bay, County Down). So, could the silver be payment for Irish mercenaries employed in imperial service? Peter outlined the evidence from the Notitia Dignitatum, a record of Roman military units, and cited key passages from the Latin sources. These texts suggest that the Irish presented a significant threat to Roman imperial interests during Late Antiquity. This evidence contradicts the modern claim that ancient Ireland was unimportant and had ‘no real history’ before the sixth century.

Peter also discussed the significance of the hacksilver discovered in the Coleraine Hoard. The ornate patterning displayed on these silver pieces was an inspiration for early Celtic knotwork – the distinctive art style that became synonymous with medieval Ireland. So, perhaps the Coleraine Hoard was not unique, and many other payments of silver ingots, coins and silverware reached fifth century Ireland. Who knows what might yet be discovered?

Where to View the Artifacts

Peter explained that some pieces of the Coleraine Hoard are kept in storage in the Ulster Museum. But the pieces held by the British Museum are on prominent display in their European Gallery next to the Sutton Hoo Helmet.

Questions

Questions at the end of the talk concerned ancient Drumanagh, a site just north of Dublin where Roman material has been unearthed. New evidence will soon be published by the Discovery Program. Dr Crawford then gave his own view on how ancient Ireland might have interacted with the Roman Empire during this earlier period (first to second centuries AD).

A Suprise

One of the people attending the talk approached Dr Crawford to show him a remarkable find. It was a late era Roman silver coin that she herself had found in an Antrim field at a different location from the hoard. The Ulster Museum had studied the coin and returned it to her. So, perhaps yet another example of Roman involvement in early Ireland?

Dr Crawford’s Talk is now available online on the Youtube Channels of both CANI and the Linen Hall Library.

Dr Raoul McLaughlin

Almost Up-setting the Order: The Kharijite Statelets of the Second Fitna (i) The Azariqa

Most of the focus on the Second Fitna – the second civil war that engulfed the Arab caliphate upon the accession of Yazid I, son of Mu’awiyah I, in April 680 and lasted until late 692 – usually falls on the tripartite war between the Umayyads in Syria, the Zubayrids in Arabia and the Alids in Iraq and Iran.

The main thrust of the source material falls first on the battles between the Umayyads and the various Alid groups – Karbala (680), Ayn al-Warda (685), Khazir (686) – only for the Zubayrids to interrupt this by defeating the Alids decisively at Madhar and Harura in late 686.

This switched the focus to the contest between the Umayyads and Zubayrids, with the former winning a significant victory at Maskin in March 691, undermining Zubayrid control of virtually all of their territory outside the Arabian Peninsula.

But as the Zubayrids would seem to have been in firm control of the Islamic heartland for a decade by this point, having successfully resisted an Umayyad invasion in 683, it would be expected that they would meet a second Umayyad invasion in the aftermath of Maskin with a similar resolve.

However, when the Umayyad army of al-Hajjaj b. Yusuf arrived in western Arabia in late 691/early 692, it found Zubayrid opposition to be lacking. This was because the forces of caliph Abd Allah b. al-Zubayr had their hands very much full with a fourth contender in the Second Fitna – the Kharijites.

These Kharijites – from the Arab root ‘to go out’ (they called themselves al-Shurat – the ‘Exchangers’ in the Qu’ranic context of trading mortal life for life with God – were what are usually considered the first sect within Islam, emerging during the First Fitna (656-661). Care must be taken in outlining who the Kharijites were and their actions as we are reliant on non-Kharijite sources due to the lack of survival of their own writings.

What became the Kharijites had initially been supporters of Ali against the Umayyad Mu’awiyah, only to rebel against his acceptance of arbitration at the Battle of Siffin in 657, claiming that battle was the only way to deal with rebels like Mu’awiyah and that

‘judgment belongs to God alone’.

When Ali later refused to go back on the arbitration, the proto-Kharijites elected their own caliph, only to be defeated by Ali at Nahrawan in 658. This shedding of blood sealed what was increasingly to be seen as a schism between the Alids and the surviving Kharijites. Indeed, the ire of the Kharijites turned away from Mu’awiyah and towards Ali, with them calling for his assassination, which was achieved by one of their number in 661.

They continued to pose a threat to the authorities, mostly focusing in and around Kufa and Basra. Mu’awiyah and his governors kept them in check for the most part, although some of their more fervent persecution may have exacerbated Kharijite militance rather than quell it.

The outbreak of the Second Fitna in 680 offered the Kharijites another opportunity to take their fight to the authorities their considered ‘unfaithful’, although circumstances would soon see them separate into two sub-factions. The catalyst for this separation was, somewhat surprisingly, Kharijite support for the the Zubayrids in Mecca. The increasingly violent suppression meted out by the Umayyad governor, Ubayd Allah b. Ziyad, helped the Kharijites of Basra remember their initial anti-Umayyad mission.

Indeed, so harsh was Ubayd Allah’s treatment that even men such as Nafi b. al-Azraq, the son of a Greek freedman (or an Arab of the Banu Hanifa), and a quietest – the religiously-motivated withdrawal from political affairs or skepticism that mere mortals can establish a true Islamic government – was encouraged to be more active in defending Islam and the Kharijite movement. This saw him, and a significant number of Kharijites from around Basra, aid al-Zubayr in defending Mecca from the Umayyads in 683.

While this Zubayrid-Kharijite was successful in keeping Mecca out of Umayyad hands (for now), it was an alliance that could not last as they held diametrically opposed beliefs, particularly over al-Zubayr proclaiming himself caliph and condemning the murder of Uthman. Upon their retreat back east from Mecca, the Kharijites split. The majority under Nafi b. al-Azraq returned to Basra, while the remainder under Abu Talut Salim b. Matar removed themselves to central Arabia, taking up around Yamama.

Arriving back at Basra, al-Azraq and his followers found that inter-tribal strife had seen to the ousting of Ubayd Allah, which allowed al-Azraq to briefly takeover the city, freeing other imprisoned Kharijites. However, rather than be ruled by radicals, the Basrans submitted to al-Zubayr and soon al-Azraq and his followers were removed from the city by the new Zubayrid governor.

They did not go far. Settling in Ahwaz and now calling themselves the Azariqa after their leader, these Kharijites launched a series of raids on the suburbs of Basra. The admittedly biased sources categorise al-Azraq’s group as one of the most fanatic Kharijite factions, claiming that they followed the doctrine of isti’rad, which allowed for the indiscriminate killing of non-Kharijite Muslims, men, women and children. For a former quietest, it would seem rather strange for al-Azraq to have made such a drastic volte face with regard to violence; that said, this could be an example of the ‘zeal of the convert’.

Whatever the extent of their violence, the Zubayrids of Basra could not allow these raids to go unchallenged and in early 685, they attacked and defeated the Azariqa, with al-Azraq himself dying in the process. However, rather than capitulate, the Azariqa regrouped, elected a new leader – Ubayd Allah b. Mahuz – and then succeeded in forcing the Zubayrids back, resuming their Basran raids.

This forced al-Zubayr to send his most capable general, al-Muhallab b. Abi Sufra, to take command at Basra against the Azariqa. He succeeded in defeating and killed Ubayd Allah b. Mahuz at Sillabra in May 686, which forced the Azariqa out of Ahwaz and into Fars.

When al-Muhallab did not chase after them, the Azariqa again regrouped under the leadership of Zubayr b. Mahuz, brother of the fallen Ubayd Allah, and launched audacious strikes against al-Mada’in, successor city of the Persian capital of Ctesiphon, and Isfahan, sacking the former but being repelled from the latter. In the process of the latter defeat, Zubayr b. Mahuz was killed and the Azariqa were forced to flee again, this time from Fars to Kirman.

However, in 687, their next new leader, Qatari b. al-Fuja’a, restored the Azariqa presence in Fars and Ahwaz, resuming the raids on Basra. Al-Muhallab was able to prevent their advance into Iraq, but could not dislodge them from Fars and Kirman. From this secure position, Qatari began to put down roots of statehood, minting his own coins – the first known Kharijite issues – and assuming the caliphal title of amir al-mu’minin – ‘commander of the faithful’. He also had other names, being known as Na’ama – ‘ostrich’ – and Abu al-Mawt – ‘father of death’, the latter of which may be connected to his poetry, which glorifies courage, death and war in the name of Allah. Indeed, he is considered by some to be the first Kharijite leader to promote jihad.

Qatari and the Azariqa remained a problem after the Umayyads reconquered Iraq in 691, with al-Muhallab retained in the Basra command but unable to make any headway. It was only in 694, when al-Hajjaj b. Yusuf was appointed governor of Iraq and began working alongside al-Muhallab that Umayyad forces began to make some headway. The Azariqa were driven out of Ahwaz and Fars once more and confined to Kirman.

The pressure of military defeat seems to have sparked division amongst the Azariqa. In 698/699, al-Hajjaj sent al-Muhallab and Sufyan b. al-Abrad to finish off the divided Kharijites. Qatari’s loyal core was confronted by al-Muhallab while on a far-reaching raid in Tabaristan in northern Iran. Qatari was able to flee towards Semnan, only to march headlong into the forces of Sufyan. Qatari’s loyalists were defeated and he was beheaded. The victorious Umayyad commanders then marched south and destroyed the remaining Kharijite forces in Kirman, destroying the Azariqa once and for all.

This piece was originally posted on the Blogographer and is reposted here with permission

The Imperial Apostate, the Great Saint and the Three Loaves of Bread

It may have been short, but Julian’s reign as sole emperor was nothing if not eventful: dispelled fear of war with Constantius II, overseeing his predecessor’s funeral, convening a tribunal to look into corruption in the previous regime, his attempted reinstitution of paganism as the ‘state religion’, trouble in Antioch, invasion of Persia, the disaster that overtook the expedition and then his demise during a Persian raid of the retreating Roman camp.

You may even have heard of the Christian legend behind his death, which saw a certain St. Mercurius rise from his grave (he was reputedly born in 225 and martyred in 250) to kill the emperor. This is likely based on the more factual suggestion that a Lakhmid, possibly Christian, Arab in Persian service did the deed.

What you might not know is that the story of the legendary re-emergence of a long dead martyr saint to kill the apostate Augustus may have begun with a falling out between two former schoolmates over three loaves of bread…

While travelling across Asia Minor in 362 to take up position in Antioch for his campaign against the Persians, Julian met with an old acquaintance somewhere near the city of Caesarea, Basil of Caesarea. But why would an avowed pagan such as Julian know a prominent (and soon to be sanctified) bishop of the Christian Church?

Well, not only had Julian been largely raised as a Christian, he and Basil (along Basil’s fellow Cappadocian Father, Gregory of Nazianzus) had been schoolmates together in Athens in the mid-350s. Such an education must have had a pagan flavour to it and during this period Julian was initiated into the Eleusinian Mysteries, and while he came from a prominent and pious Christian family, Basil’s initial career in law and rhetoric have all the hallmarks of paganism, with Basil himself stating that he “had wasted much time on follies and spent nearly all of my youth in vain labors, and devotion to the teachings of a wisdom that God had made foolish” (Basil, Ep. 223.2).

However, a chance meeting with the charismatic ascetic Eusthatius, bishop of Armenian Sebaste, saw Basil “awoke as out of a deep sleep. I beheld the wonderful light of the Gospel truth, and I recognized the nothingness of the wisdom of the princes of this world” (Basil, Ep. 223.2).

Upon receiving baptism, Basil spent the next 5 years studying ascetics and monasticism around the Roman east, giving away his wealth to the poor, establishing a community around him, writing about communal monasticism, attending the Council of Constantinople in 360 (where he first backed Eustathius and the Homoiousian/‘Semi-Arian’ faction, only to abandon that side in favour of the Homoousian support of the Nicene Creed), before being ordained as a deacon in 362.

During this same period, Julian had been promoted to Caesar by Constantius II and given (figurehead) command of Roman forces in Gaul, where he faced mixed fortunes in the field, with some mistakes almost bringing about disaster, but also punctuated with the significant success at the Battle of Strasbourg in 357 against the Alamanni and in crossing the Rhine on several occasions (Crawford (2016) ch.7-8). And now in 362, the apostate Augustus and Christian deacon met once more outside Caesarea.

We can already see some issues with the legend as it regards Basil as already being the metropolitan of Caesarea at the time of this meeting with the emperor Julian, but Basil’s predecessor as bishop of Caesarea, Eusebius, was still alive in 362. Indeed, Eusebius’ predecessor, Dianio, may have been still alive too. Basil himself was not consecrated as bishop until 14 June 370.

Upon meeting the emperor, the still-deacon Basil presented Julian with three loaves of bread. The emperor did not take kindly to this gift proclaiming that the deacon would be rewarded with grass from a field!

Basil tried to explain that he meant no insult in this gift, merely offering Julian a sample of what Basil himself ate. Rather than ameliorate the emperor, it enraged him further, with Julian reputedly exclaiming…

“Now accept this gift, and when I return from Persia the victor, then, I will burn your city, I will remove your infantile people and enslave them, because the gods which I worship they dishonour, and you will receive the appropriate reward.”

But why was Julian seemingly so incandescently angry at Basil’s gift? I think it is a given that the Christian source material is playing up the apostate emperor’s ire, but did he dislike Basil’s gift due its sheer paucity, giving only bread to the Imperator Flavius Claudius Iulianus Pius Felix Augustus?!? Or was it because of the possibly inherent ideas of Christian charity and priestly sharing of want that so perturbed Julian?

Or was it even something more specific to the type of bread – barley – that Basil offered? Whether the geographical preference was for rye or wheat, using barely was definitely considered a distant second best. Basil, along with all the other clergy, ate bread made from barely to demonstrate their humility. However, Julian may have felt, not without cause, that ‘barley was only fit for horse’, hence why he offered the holy man some grass/hay in return (cf. Lacey and Danziger (1999) 118).

There is also the suggestion that in giving Basil the grass from a specific field, Julian was actually gifting him the right of pasturage on that field. The Christian sources seem to present this as an error on the part of Julian, which contributed to his anger, but it is possible that they have inadvertently revealed the truth behind this story. Might it be that in meeting his old school friend, Julian readily accepted the gift of bread and, like the deacon had done in sharing in the barley harvest, reciprocated with a similar gift of pasturage, possibly including barley itself?

Whatever the truth the behind this story, the legend built up that after this imperial threat to return and destroy Caesarea, Basil and his flock prayed before an icon possibly of St. Mercurius in the church of the Virgin Mary on ‘Mount Didymus’. Slight differences in the story have either the Virgin herself call forth the martyr saint Mercurius, with Basil then going to the saint’s shrine to find his body missing or Basil prayed for the saint to ask God to prevent Julian from returning from Persia to destroy Caesarea, with the reply being that the image of the spear-wielding Mercurius became invisible…

Within seven days of Basil telling his flock that Mercurius’ body was missing, word arrived that Julian the Apostate was dead… killed by a spear… Best to accept a gift of bread without comment it seems…

Bibliography

Baynes, N. H. ‘The Death of Julian the Apostate in a Christian Legend’, JRS 27 (1937) 22-29

Crawford, P. Constantius II: Usurpers, Eunuchs and the Antichrist. Barnsley (2016)

Dawkins, R.M. ‘A Byzantine Carol in Honour of St. Basil’, JHS 66 (1946) 43-47

Hildebrand, S. M. Basil of Caesarea. Grand Rapids (2014).

Lacey, R. and Danziger, D. The Year 1000: What Life Was Like at the Turn of the First Millennium – An Englishman’s World. Boston (1999)

Rousseau, P. Basil of Caesarea. Berkeley (1994).

http://full-of-grace-and-truth.blogspot.com/2009/12/vision-of-st-basil-great-and-julian.html