ancient-greece

“What a [Herculean] Manoeuvre!”: Inventing the Bear Hug

What do the following men all have in common?

- Superstar Billy Graham

- Ted Arcidi

- Tony Atlas

- Mark Henry

- Bill Kazmaier

- Brock Lesnar

- The Yeti

- Bruno Sammartino

- Georg Hackenschmidt

Aside from all being professional wrestlers, they also all used the bearhug as a ‘finishing’ move at some point in their careers.*

And yet, while the lattermost of that list – Georg Hackenschmidt – is usually credited with creating the professional wrestling version of the bearhug, the hold itself is much older than the earliest years of the 20th century.

Its invention ‘dates’ back to mythological times, or at least to the period when these myths were being formulated or written down in the mid-1st millennium BC. Furthermore, the ‘first’ bear hug came during one of the most famous Greek myths: that series of intentionally (but not actually) impossible tasks given by Eurystheus, king of Tiryns – the Twelve Labours of Hercules.

During his fulfilling of the 11th Labour – stealing apples from the garden of the Hesperides, Hercules has his brush with wrestling history. While searching for the garden in the Libyan desert of North Africa (Apollodorus 2.5.11; Diodorus 4.17.4), Hercules met a certain Antaeus, a giant son of Poseidon and Gaia.

The mythological nature of Antaeus and how he is identified solely by his mythological actions towards various opponents and possibly the Herculio-centric nature of the story-telling may be reflected in his name stemming from the Greek ἀντάω meaning ‘I oppose’, Ἀνταῖος means ‘opponent’. Antaeus also appears in Berber/ Amazigh mythology as ‘Anti’, and with his wife, the goddess Tinge, father the daughters Alceis/Barce and Iphinoe.

True to his name, Antaeus would challenge all passers-by to a wrestling match, which would have been quite the test due to him being a giant demigod who was skilled in wrestling (Diodorus Siculus 4.17.4); however, Antaeus had an extra secret weapon in his blood. While he received significant strength from Poseidon, it was his mother Gaia from whom he gained an unfair advantage over his opponents: so long as he remained in contact with the ground – i.e. Gaia herself – Antaeus could replenish his “enormous strength” (Lucan, Pharsalia 4.600).

And as Archaic Greek wrestling typically involved attempting to force your opponent to the ground and pin them, Antaeus’ ability to gain strength from contact with the ground made him almost unbeatable, for if his sheer size and wrestling skill were not enough for victory, he could simply outlast his opponents. Due to this combination of enormous strength, colossal skill and unending stamina, it was even claimed that he would have been a significant threat to the gods themselves (Lucan, Pharsalia 4.597).

If such an unfair advantage was not bad enough, Antaeus killed those he defeated (everyone) and used their skulls in the construction of a temple to his father, seemingly for the roof (Pindar, Isthmian Odes 1.4.52-54).

Given the opening question of this piece, some of you may already be recognising how Antaeus is going to be bested, but even with such a ‘plan’ in mind, it would require someone of significant wrestling skill and immense strength to achieve it – unfortunately for Antaeus, someone of just such a skill set had found himself walking through the area of the Libyan desert where Antaeus offered his challenges. He might not have been as big as Antaeus, but Hercules was every bit as strong and more (cf. Tzetzes, Chiliades 2.364-365).

In terms of detail of the Antaeus/Hercules contest, it is Lucan’s Pharsalia (4.660-739) that provides the most in-depth account, while most others merely present the location and the outcome. Of course, the lack of other material giving depth to the contest suggests that Lucan has invented much of what he writes, even if he puts the telling of the story in the mouth of an African local speaking to Gaius Scribonius Curio during the Caesarian civil war of the early 40s BC. Even then, Lucan’s retelling is not all that long, but there is just enough to divide it into four small sections – the prelude and then three ‘rounds’.

Prelude and Preparations

Rather than present the contest as an incidental sideshow surrounding Hercules’ 11th Labour, Lucan presents it more as the ‘Mighty’ Hercules travelling to Libya specifically to deal with Antaeus, who was more of a monstrous/ogre-like menace to passers-by and innocent Libyan farmers.

Both men three off their coverings – Hercules the skin and mantle of the Nemean Lion (his first Labour) and Antaeus a hide of local beasts (Lucan, Pharsalia 4.683-686) – as Greek wrestling contests were fought naked.

Lucan also intimates that Antaeus had never had much need to use his energy replenishment special move due to the inability of his opponents to knock him down at all. However, in his bodily preparation for the contest, Antaeus could betray some wariness of Hercules. While Hercules rub oil onto his limbs as was the norm for a wrestling contest, Antaeus covered his body in sand to have more contact with the ground than just the soles of his feet. That said, this could be something that Antaeus did before all of his contests, rather than just for that with Hercules. Whichever it was, one might suggest that it was a ‘heelish’ tactic to gain a further advantage over his opponent, although a wrestler rubbing dirt into his hands was a way to increase grip.

Round 1

The first part of the contest began with locked arms, with both trying “to secure a neck-hold.” Both were surprised by their failure to immediately gain the upper hand and by the strength of their opponent. In response, Hercules settled into a strategy of wearing Antaeus down, which would have been a good move against virtually any other opponent…

Initially, it seemed to work, with Hercules’ strength able to make Antaeus “pant and sweat” to the point that he lost his form, allowing Hercules to unbalance him with a strike to the upper leg and then transition into a waist lock, kick his legs out from under him and slam Antaeus into the ground.

This may well have resulted in victory for Hercules, and was probably the kind of move that had won him matches in the past, but Antaeus had his Gaia-given power.

The combination of the sand he had covered himself with and the contact with the ground saw

“fresh blood coursed through his veins, his muscles bulged, his body regained strength.” Much to Hercules’ shock, this rejuvenation allowed Antaeus to escape his grasp and re-establish his vertical base.

Lucan even suggests that Antaeus’ escape left Hercules feeling even more apprehensive than then he had fought the hundred-headed Hydra… much to his step-mother Hera’ delight!

Round 2

The second ‘round’ of the fight saw a similar battle of strength. Hercules, “exhaustion overcoming him and making the sweat start from his neck”, had not had to struggle this much before, even when he briefly held up the heaves for Atlas the Titan.

Despite Hercules’ struggles, it was again Antaeus who began to weary, but this time he did not wait until Hercules was able to take him down. Instead, he deliberately threw himself to the ground, drinking deeply of the replenishing energy Mother Earth provided for him. “One might say that she herself felt worn out by the strain of this wrestling match.”

However, it seems that Antaeus had made what he was doing all too obvious. Hercules therefore changed his strategy – rather than try to force Antaeus to ground, Hercules determined to keep him upright, or failing that, to make sure if he fell, that he fell on top of Hercules.

Round 3

With this change in strategy, the third ‘round’ proved decisive in this heaviest-weight contest.

When they engaged once more or perhaps grabbing him whilst he lay on the ground the second time, Hercules lifted Antaeus off the ground. He then “resisted his frantic efforts to cast himself down,” all the while squeezing Antaeus in a what would technically be called an elevated bear hug, although it is not explained whether it was a rear or frontal bear hug.

This lack of clarity is demonstrated in the various depictions of the Herculean bear hug, with there being no settled style – both frontal and rear bear hugs are depicted.

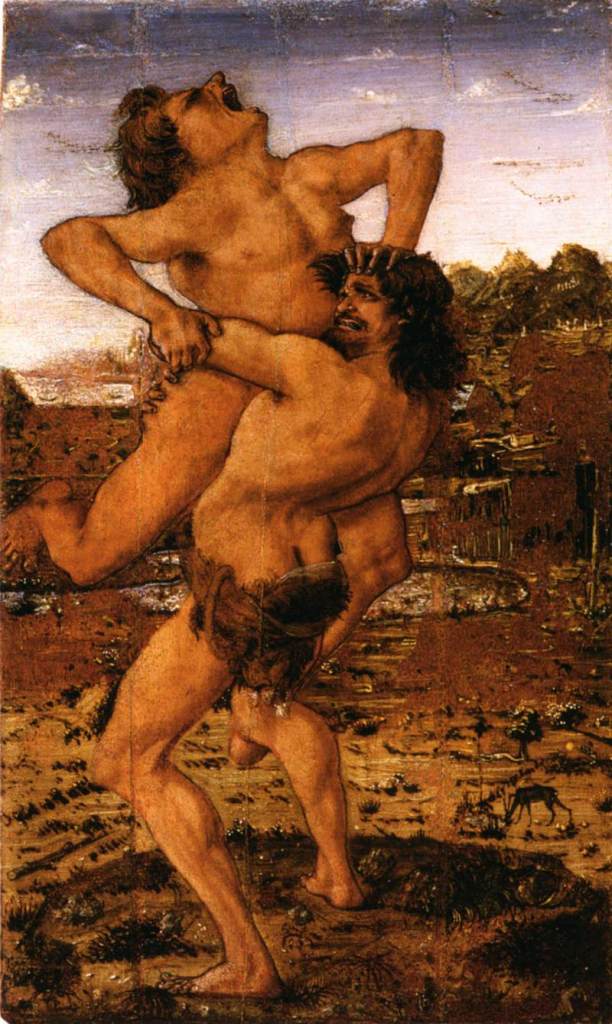

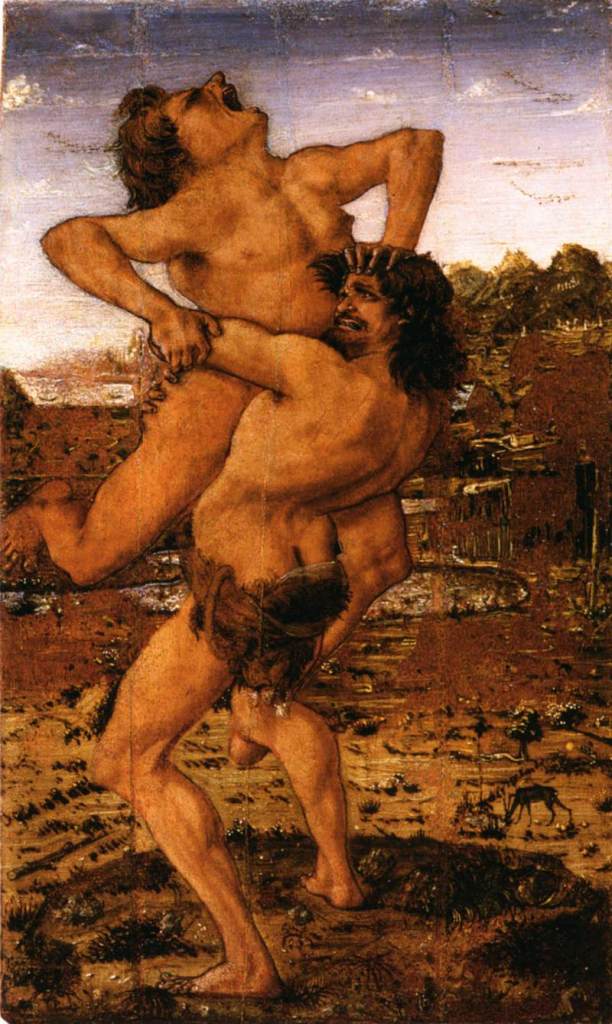

Frontal bear hug

Hercules slaying Antaeus, painting by Florentine artist Antonio del Pollaiuolo in c.1460, now in the Uffizi gallery, Florence.

Hercules Fighting Antaeus in the Hofburg Quarters, Vienna

18th century French sculpture in the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore

17th century Italian bronze in the Metropolitan Museum, New York

Rear bear hug

Roman sculpture of Hercules and Antaeus in the Uffizi collection in Florence

In his 1634 work Hercules Fighting Antaeus, Spanish painter Francisco de Zurbarán portrays it as a rear bear hug – i.e. Hercules has lifted Antaeus from behind.

19th century bronze in the Metropolitan Museum, New York

How ever Hercules held him aloft, the separation from the ground and the squeezing strength of the Heruclean bear hug eventually took their toll on Antaeus. While exact details are not given, it is safe to assume that Hercules squeezed the life out of Antaeus, likely breaking his back in the process; however, even as “he felt the giant’s body stiffening… [Hercules] continued to hold it aloft, and thus prevented Mother Earth from reviving her dying son” (Lucan, Pharsalia 4.735-736; cf. Hyginus, Fabulae 31; Apollodorus 2.5; Diodorus Siculus 4.18.1, 27.3).

“There withal was wrought Antaeus’ brawny strength, who challenged him to wrestling-strife; he in those sinewy arms raised high above the earth, was crushed to death”

Quintus Smyrnaeus 6.318-323

It was only long after the “chill of death” had taken Antaeus that Hercules felt safe to release his bear hug and rest Antaeus’ body back into the bosom of his mother (one would think that a referee would have stopped a fight a good bit before that and possibly even disqualified Hercules for refusing to release the hold…).

Not only did Hercules take Antaeus’ life, some Berber/Amazigh traditions have him taking his wife as well. The liaison between Tinge and Hercules led to the birth of Sufax, the legendary founder of the city of Tingis (modern Tangier in Morocco), who named it after his mother (Livy 30.12; Plutarch, Sertorius 9.4), although Plutarch says that this lineage of Sufax was likely created to satisfy Juba II of Mauretania, who claimed descent from him (Plutarch, Sertorius 9.5).

There is also a tradition that it was Iphinoe, daughter of Antaeus and Tinge, that became a consort of Hercules, resulting in the birth of Palaemon, although his mother is also recorded as being Autonoe, daughter of Peireus (Tzetzes, Lycophron 663; Apollodorus 2.7.8).

As to the fate of Antaeus’ remains, during his African campaign, from which we get the report in Lican of a more in-depth contest between Antaeus and Hercules, Curio “marched up to a rocky hill, pitted with caves, traditionally known as the ‘Tomb of Antaeus’” (Lucan, Pharsalia 4.589-590). However, somewhat at odds with this is how the Roman general, Quintus Sertorius, in 81 BC, was told by the people of Tingis that the vast remains of the giant Antaeus could be seen in a burial mound in the Libyan desert. Finding the mound, Sertorius had the massive bones exhumed and “was dumbfounded, and after performing a sacrifice filled up the tomb again, and joined in magnifying its traditions and honours” (Plutarch, Sertorius 9.4).

Tingis is quite removed from the area that Curio had been campaigning in 49BC – about 1,500 miles removed in fact – so it is unlikely, if not impossible, that Sertorius and Curio visited the same site. Certainly, Sertorius seems to have only campaigned in Mauretania, modern Morocco, while Curio was seemingly only in what is now Tunisia.

More than one place claiming to be the burial site of the vanquished Antaeus likely demonstrates the mythological nature of the story; however, it also highlights the spread of that story geographically and culturally, as it stretched across North Africa and between Greek and Amazigh/Berber cultures.

This spread of the story took with it the supposed invention of the elevated bear hug and some of the technique involved in its use. But one thing that the spread of this story could not impart on those who wished to replicate Hercules’ match-winning manoeuvre was the supposed strength of those involved in its invention.

While in no way denigrating the feats of strength and athleticism achieved by the men listed in the question at the beginning of this piece, none of them could emulate the power scale of two demigods – one the son of Zeus, the other the son of Poseidon and Gaia. That first bear hug was almost certainly to be the most powerful to ever be seen.

* For you pro wrestling aficionados out there, it is somewhat surprising, particularly given its supposed mythological inventor, that the ‘Mighty’ Hercules Hernandez did not use the bear hug as a signature move during his career, aside from seemingly a brief period in 1984-1985 when he was performing as ‘Mr. Wrestling II/III’ in Mid-South Wrestling.