islam

Almost Up-setting the Order: The Kharijite Statelets of the Second Fitna (ii) The Najdat

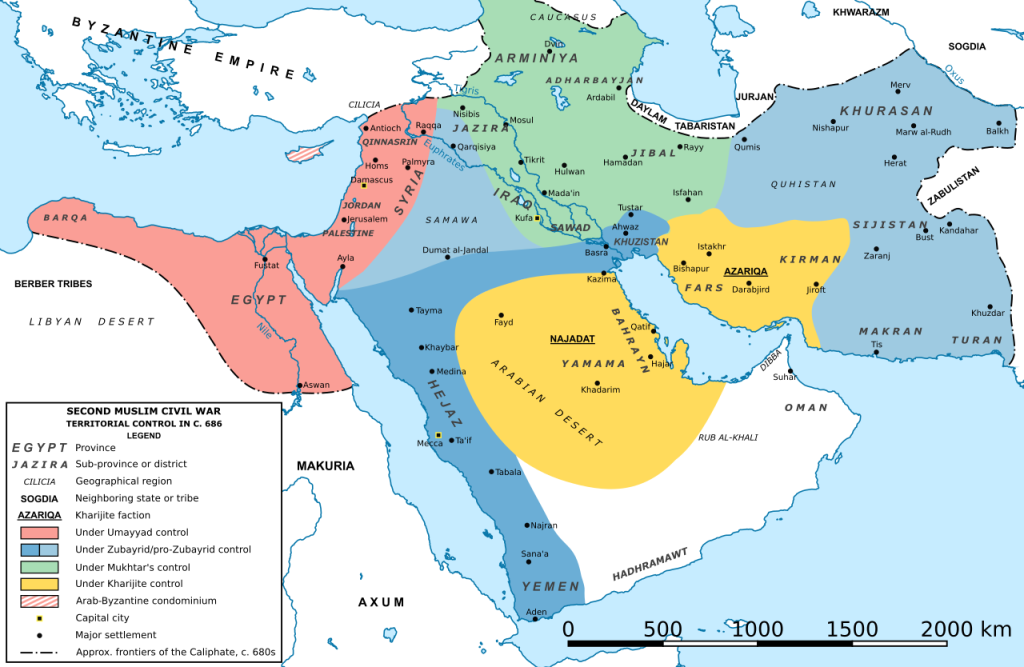

The doctrinal divide that sealed the fate of Qatari’s burgeoning Azariqa statelet in Kirman was not the first instance of such internal strife. When al-Azraq was driven out of Basra by the Zubayrids, not all of his followers went with him to Ahwaz. A group under Najda b. Amir al-Hanafi disagreed with al-Azraq’s leadership and moved south-west to join the Kharijites of Abu Talut in Yamama, a region from where Najda hailed.

Upon moving into Yamama, Abu Talut had established himself on a large tract of agricultural land called Jawn al-Khadarim, distributing the land and its resident slaves amongst his followers. And when Najda’s group arrived in the region it brought with them considerable loot taken from a caravan heading to Mecca from Basra. He had this look distributed amongst the Kharijites of Yamama and advised them to continue using the freed slave labour as a basis for their power in the region. Such a move proved successful and popular, to the extent that when Najda suggested that he be the leader of Kharijite Yamama, he was unanimously accepted, even by Abu Talut himself. This led to this group being called after its new leader – the Najdat.

Using his new leadership position and the solid agricultural base provided by his lands, Najda was soon on the warpath. Before 685 was out, he raided Bahrayn in eastern Arabia, winning a great victory at Dhu’l-Majaz and capturing a large amount of corn and dates that had been looted from a nearby market.

This raid was followed up a year later by the forcing of a more permanent Kharijite presence in the region. Intervening in a tribal conflict, Najda took control of the major port city of Qatif, which became one of his major headquarters. The claiming of Bahrayn was to be the first in a series of victories that would stretch the Najdat statelet to much of the Arabian Peninsula and threaten to split the Zubayrid caliphate in half. And the Zubayrids were not idle in confronting this threat. The caliph’s son and governor of Basra, Hamza, sent an army of 14,000 men to challenge the Kharijites, only for it to be ambushed by Najda and put to flight.

Najda followed up this victory by sending his lieutenant Atiyya b. al-Aswad to Oman, where he defeated its chieftains to bring the region into under Najdat control; however, this only lasted a few months as Atiyya’s deputy was defeated and ejected from the region. This defeat and Najda’s unequal distribution of reward and possible communication with Abd al-Malik, the Umayyad caliph, led to growing divide between Atiyya and Najda. This would culminate in 687 with Atiyya taking a group of supporters to Sistan, on the Iran/Pakistan frontier, where they established their own Kharijite faction – the Atawiyya.

This was only a momentary bump in the road for the Najdat, as their control over Bahrayn was tightened, another deputy marched to Hadhramawt and Najda himself led an army into Sana’a, with the capitulation of both making the entirety of Yemen tributary of the Najdat. These successes actually made Najda more powerful in Arabia than al-Zubayr, although the victory over the Alids in mid-April 687 had greatly expanded the territory that recognised al-Zubayr as caliph.

This did not perturb Najda, with Kharijite raids striking into the Hejaz. Perhaps only religious concerns over attacking the holy sites of Mecca prevented the Najdat from making more headway than they did at this point. And even with this hesitation, it did not stop Najda from blockading much of the Hejaz.

However, one thing did make into Mecca – Najda himself. In mid-687, in a true testament to the perception of Najdat power, its leader was ‘allowed’ to lead a group of his Kharijite followers on the Hajj pilgrimage. If he tried to stop him, al-Zubayr proved powerless to prevent such an incursion into what was his capital city. With this demonstration, the Najdat appeared the equal of the Zubayrids and the Umayyads.

Despite worries over using violence towards the holy sites, Najda forged on into the Hejaz after returning from his Hajj. His forces approached Medina, but when it refused to capitulate without a fight, Najda again withdrew from attacking a holy city. Instead, Najda moved against Ta’if, near Mecca. Here, he received a more open welcome, with the Ta’if leadership giving their allegiance to the Najdat. By 689, the Kharijites controlled enough of the southern Hejaz to appoint their own governor over a region taking in Ta’if, Sarat and Tabala, while also collecting tribute from even further south. Virtually all of Arabia was under Najdat control. It would seem to only be a matter of time before Najda looked to finish off the Zubayrids. And yet, this was to be the peak of Najdat power.

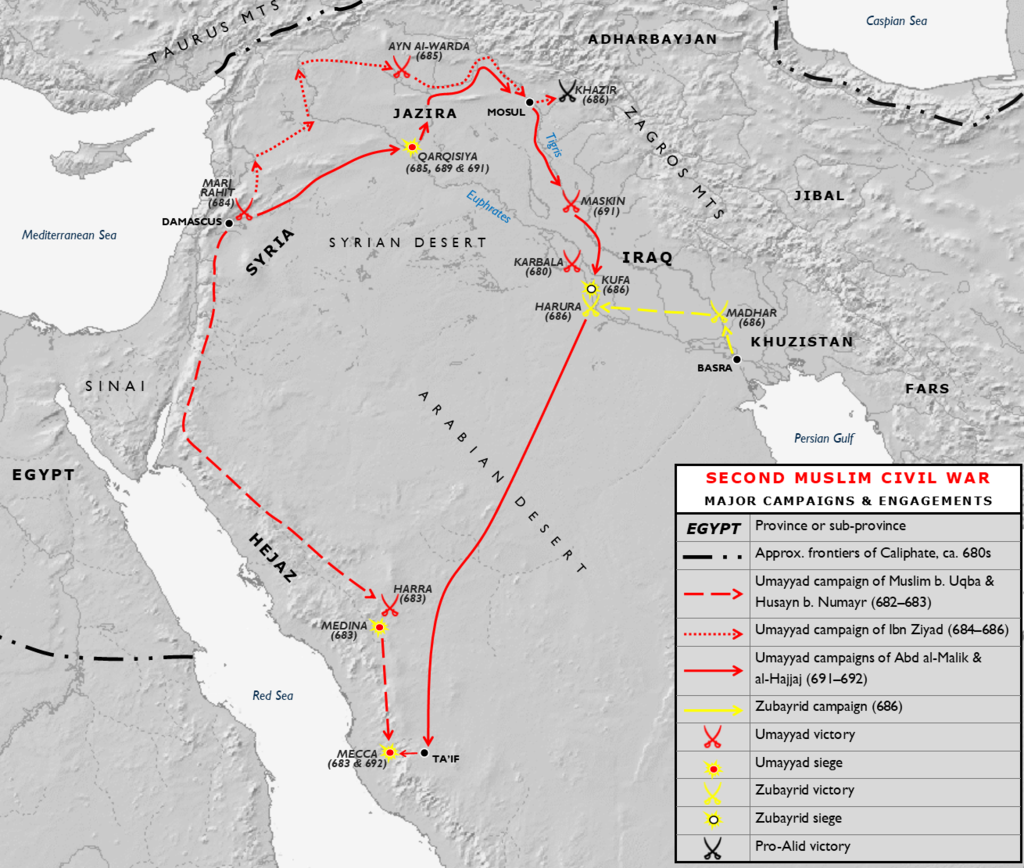

As al-Hajjaj arrived in the Hejaz in late 691, he may have been surprised by the lack of Zubayrid opposition, but that does not mean that there was significant Kharijite opposition instead. Bypassing Medina and Mecca due to orders from caliph Abd al-Malik not to attack the holy sites (yet), the Umayyad general moved against Ta’if, his hometown, and quickly removed whatever allegiance it owed to the Najdat.

Indeed, during these initial Umayyad moves and even their subsequent attacks on first Medina and then Mecca itself through 691 and 692, attacks brough an end to the Second Fitna upon the death of al-Zubayr in late 692, there was no mention of Kharijite resistance to the Umayyad incursion.

For a statelet at the height of its powers, it seems peculiar for the Najdat to be so inactive during the battle for the Hejaz. How had it come to be that Najda and his followers were absent from this climactic end of the second Muslim civil war?

Abd al-Malik had clearly recognised the Najdat threat as dealing with them appears to have been part of al-Hajjaj’s remit as governor of the Hejaz, Yemen and Yamama, a remit that encompassed significant lands under Najdat control. However, it appears to be Abd al-Malik’s diplomacy that undid the Najdat statelet more than the military actions of al-Hajjaj or the Zubayrids.

We have already seen how contact with the Umayyad caliph had led to a schism in the Najdat with Atiyya’s departure to Sistan in 687 and it appears that a similar episode happened again in around 690. Almost certainly knowing exactly what he was doing, Abd al-Malik reached out to Najda, offering amnesty and the Yamama governorship in return for recognition of his caliphate. Najda rejected the offer, but maintained cordial relations with Damascus, with this being enough to cause dissension in the Najdat ranks.

Being a faction built on what they saw as ideological and religious purity in the face of the corruption of Islam, this Kharijite dissension quickly turned into a full split between those supposedly open to negotiations with the ‘usurper’ Abd al-Malik and those hardliners who now saw Najda as irrevocably tainted ideologically and religiously. It is likely that there was more at play than just dissent at Umayyad dealings – there was dispute over the dissemination of pay to certain parts of Najdat military, while Najda reputedly gave preferential treatment to his close associates despite reports of their religious impropriety.

This split redirected Najdat attention and then drained away Najdat power at a time when a potential victory was in the offing. It is not beyond the realms of possibility that opposition to the Umayyads amongst Zubayrid supporters could have seen Najda’s ranks swollen to an extent when they could have challenged the forces of al-Hajjaj.

As it was, instead, the cunning diplomacy of Abd al-Malik had not only neutralised the Najdat but ultimately destroyed it. Even before the final defeat of al-Zubayr in Mecca, Najda had been murdered by Najdat radicals under Abu Fudayk in Bahrayn.

It was quickly proven how much the Najdat statelet had relied on Najda’s leadership abilities and reputation. Abu Fudayk tried to take up the mantle of Najdat ‘commander of the faithful’ and was initially successful in repelling an Umayyad invasion from Basra in 692; however, this was only delaying the inevitable. The following year, a combined army of Basran and Kufan forces defeated Abu Fudayk at Mushahhar, just south of Qatif, before capturing the last major Najdat holdout by the end of the year. The Najdat Kharijites themselves did not completely disappear, surviving in some form for another two centuries or more, but they were never the same coherent threat they had been under their eponymous leader.

Given the solidity and indeed power it had managed to accrue under the leadership of Najda, it is somewhat surprising that the Najdat collapsed before its much less secure sister statelet in the Azariqa. But only somewhat. It can never be surprising that a faction whose identity was formed through an extreme even fanatical conformity to religious practice and tradition sees its leadership, no matter how successful, or even the very faction itself overthrown by the necessity of adherence to an impossibly strict code of conduct and belief.

The Kharijites as a whole survived the Umayyad destruction of the Najdat and the Azriqa in the 690s, but they were significantly weakened. There would be a significant Kharijite rebellion across the caliphate in the 740s and 750s, although the leading roles was taken by more moderate Kharijite groups – the Sufriyya and Ibadiyya, with the more militant groups gradually eliminated by the Abbasid caliphate. These moderate groups would have some ephemeral success in the caliphal heartlands, capturing major centres like Kufa, Mosul and even Medina and Mecca for a time, only to be ejected; however, they both saw more lasting success on the fringes of the caliphate – a Sufriyya dynasty ruled Morocco for 150 years from 750, while the Ibadiyya enjoyed similar success at around the same time ruling Algeria and Oman, with the modern population of the latter made of a majority of Ibadi Muslims.

While modern day Ibadi in Oman and North Africa (where they absorbed their Sufriyya brethren by the 11th century) are ultimately the descendants of moderate Kharijites, they strongly condemn the extremism and violence of Kharijites such as the Najdat and Azariqa, even though those groups came close to upsetting the established caliphal order during the Second Fitna.

Bibliography

Dixon, A.A. The Umayyad Caliphate, 65–86/684–705: (A Political Study). London (1971)

Gaiser, A. Muslims, Scholars, Soldiers: The Origin and Elaboration of the Ibadi Imamate Traditions. Oxford (2010).

Hagemann, H-L. The Kharijites in Early Islamic Historical Tradition: Heroes and Villains. Edinburgh (2021).

Watt, W.M. ‘Khārijite thought in the Umayyad Period,’ Der Islam 36 (1961) 215–231

Almost Up-setting the Order: The Kharijite Statelets of the Second Fitna (i) The Azariqa

Most of the focus on the Second Fitna – the second civil war that engulfed the Arab caliphate upon the accession of Yazid I, son of Mu’awiyah I, in April 680 and lasted until late 692 – usually falls on the tripartite war between the Umayyads in Syria, the Zubayrids in Arabia and the Alids in Iraq and Iran.

The main thrust of the source material falls first on the battles between the Umayyads and the various Alid groups – Karbala (680), Ayn al-Warda (685), Khazir (686) – only for the Zubayrids to interrupt this by defeating the Alids decisively at Madhar and Harura in late 686.

This switched the focus to the contest between the Umayyads and Zubayrids, with the former winning a significant victory at Maskin in March 691, undermining Zubayrid control of virtually all of their territory outside the Arabian Peninsula.

But as the Zubayrids would seem to have been in firm control of the Islamic heartland for a decade by this point, having successfully resisted an Umayyad invasion in 683, it would be expected that they would meet a second Umayyad invasion in the aftermath of Maskin with a similar resolve.

However, when the Umayyad army of al-Hajjaj b. Yusuf arrived in western Arabia in late 691/early 692, it found Zubayrid opposition to be lacking. This was because the forces of caliph Abd Allah b. al-Zubayr had their hands very much full with a fourth contender in the Second Fitna – the Kharijites.

These Kharijites – from the Arab root ‘to go out’ (they called themselves al-Shurat – the ‘Exchangers’ in the Qu’ranic context of trading mortal life for life with God – were what are usually considered the first sect within Islam, emerging during the First Fitna (656-661). Care must be taken in outlining who the Kharijites were and their actions as we are reliant on non-Kharijite sources due to the lack of survival of their own writings.

What became the Kharijites had initially been supporters of Ali against the Umayyad Mu’awiyah, only to rebel against his acceptance of arbitration at the Battle of Siffin in 657, claiming that battle was the only way to deal with rebels like Mu’awiyah and that

‘judgment belongs to God alone’.

When Ali later refused to go back on the arbitration, the proto-Kharijites elected their own caliph, only to be defeated by Ali at Nahrawan in 658. This shedding of blood sealed what was increasingly to be seen as a schism between the Alids and the surviving Kharijites. Indeed, the ire of the Kharijites turned away from Mu’awiyah and towards Ali, with them calling for his assassination, which was achieved by one of their number in 661.

They continued to pose a threat to the authorities, mostly focusing in and around Kufa and Basra. Mu’awiyah and his governors kept them in check for the most part, although some of their more fervent persecution may have exacerbated Kharijite militance rather than quell it.

The outbreak of the Second Fitna in 680 offered the Kharijites another opportunity to take their fight to the authorities their considered ‘unfaithful’, although circumstances would soon see them separate into two sub-factions. The catalyst for this separation was, somewhat surprisingly, Kharijite support for the the Zubayrids in Mecca. The increasingly violent suppression meted out by the Umayyad governor, Ubayd Allah b. Ziyad, helped the Kharijites of Basra remember their initial anti-Umayyad mission.

Indeed, so harsh was Ubayd Allah’s treatment that even men such as Nafi b. al-Azraq, the son of a Greek freedman (or an Arab of the Banu Hanifa), and a quietest – the religiously-motivated withdrawal from political affairs or skepticism that mere mortals can establish a true Islamic government – was encouraged to be more active in defending Islam and the Kharijite movement. This saw him, and a significant number of Kharijites from around Basra, aid al-Zubayr in defending Mecca from the Umayyads in 683.

While this Zubayrid-Kharijite was successful in keeping Mecca out of Umayyad hands (for now), it was an alliance that could not last as they held diametrically opposed beliefs, particularly over al-Zubayr proclaiming himself caliph and condemning the murder of Uthman. Upon their retreat back east from Mecca, the Kharijites split. The majority under Nafi b. al-Azraq returned to Basra, while the remainder under Abu Talut Salim b. Matar removed themselves to central Arabia, taking up around Yamama.

Arriving back at Basra, al-Azraq and his followers found that inter-tribal strife had seen to the ousting of Ubayd Allah, which allowed al-Azraq to briefly takeover the city, freeing other imprisoned Kharijites. However, rather than be ruled by radicals, the Basrans submitted to al-Zubayr and soon al-Azraq and his followers were removed from the city by the new Zubayrid governor.

They did not go far. Settling in Ahwaz and now calling themselves the Azariqa after their leader, these Kharijites launched a series of raids on the suburbs of Basra. The admittedly biased sources categorise al-Azraq’s group as one of the most fanatic Kharijite factions, claiming that they followed the doctrine of isti’rad, which allowed for the indiscriminate killing of non-Kharijite Muslims, men, women and children. For a former quietest, it would seem rather strange for al-Azraq to have made such a drastic volte face with regard to violence; that said, this could be an example of the ‘zeal of the convert’.

Whatever the extent of their violence, the Zubayrids of Basra could not allow these raids to go unchallenged and in early 685, they attacked and defeated the Azariqa, with al-Azraq himself dying in the process. However, rather than capitulate, the Azariqa regrouped, elected a new leader – Ubayd Allah b. Mahuz – and then succeeded in forcing the Zubayrids back, resuming their Basran raids.

This forced al-Zubayr to send his most capable general, al-Muhallab b. Abi Sufra, to take command at Basra against the Azariqa. He succeeded in defeating and killed Ubayd Allah b. Mahuz at Sillabra in May 686, which forced the Azariqa out of Ahwaz and into Fars.

When al-Muhallab did not chase after them, the Azariqa again regrouped under the leadership of Zubayr b. Mahuz, brother of the fallen Ubayd Allah, and launched audacious strikes against al-Mada’in, successor city of the Persian capital of Ctesiphon, and Isfahan, sacking the former but being repelled from the latter. In the process of the latter defeat, Zubayr b. Mahuz was killed and the Azariqa were forced to flee again, this time from Fars to Kirman.

However, in 687, their next new leader, Qatari b. al-Fuja’a, restored the Azariqa presence in Fars and Ahwaz, resuming the raids on Basra. Al-Muhallab was able to prevent their advance into Iraq, but could not dislodge them from Fars and Kirman. From this secure position, Qatari began to put down roots of statehood, minting his own coins – the first known Kharijite issues – and assuming the caliphal title of amir al-mu’minin – ‘commander of the faithful’. He also had other names, being known as Na’ama – ‘ostrich’ – and Abu al-Mawt – ‘father of death’, the latter of which may be connected to his poetry, which glorifies courage, death and war in the name of Allah. Indeed, he is considered by some to be the first Kharijite leader to promote jihad.

Qatari and the Azariqa remained a problem after the Umayyads reconquered Iraq in 691, with al-Muhallab retained in the Basra command but unable to make any headway. It was only in 694, when al-Hajjaj b. Yusuf was appointed governor of Iraq and began working alongside al-Muhallab that Umayyad forces began to make some headway. The Azariqa were driven out of Ahwaz and Fars once more and confined to Kirman.

The pressure of military defeat seems to have sparked division amongst the Azariqa. In 698/699, al-Hajjaj sent al-Muhallab and Sufyan b. al-Abrad to finish off the divided Kharijites. Qatari’s loyal core was confronted by al-Muhallab while on a far-reaching raid in Tabaristan in northern Iran. Qatari was able to flee towards Semnan, only to march headlong into the forces of Sufyan. Qatari’s loyalists were defeated and he was beheaded. The victorious Umayyad commanders then marched south and destroyed the remaining Kharijite forces in Kirman, destroying the Azariqa once and for all.

This piece was originally posted on the Blogographer and is reposted here with permission