Why Do We Need New Translations of Ancient Texts? Ines Choi

John Dryden remarks in the preface to Ovid’s Epistles that the art of translation can be classified into three types: metaphrasing, paraphrasing and imitating (Dryden (1776, preface). The first constitutes the “word-by-word, line-by-line” approach which he deems ill-fitting (Dryden (1776) preface). This literal approach focuses on the “mechanics” of language and calls into question the “practicality” of embarking on re-translations. Its limitations are evident when using Google Translate on ancient texts which are heavy with meaning and nuance. Additionally, it lacks a deeper sensitivity to context, perspective and values which are reflected in language and form over time. New translations are incredibly important and arguably essential to unearth fresh perspectives, address cultural misconceptions in past translations, understand the impact of domesticating and/or foreignising a translation (“Foreignisation” and “domestication” are terms coined by translation theorist Lawrence Venuti in his 1995 book The Translator’s Invisibility), and lastly to reinvigorate a text in a creative way, promoting inclusion and appeal to a broader community.

New translations of ancient texts provide original, raw, sometimes broader and more complex perspectives through which to see a narrative. Emily Wilson’s translation of Homer’s Odyssey is a clear example of this approach. In a recent lecture, Wilson articulates the need for an authentic and new vision for the Odyssey using multiple perspectives because she felt previous translations were too limiting (Wilson (2019b)). The first lines of the poem strongly reveal her intentions:

Tell me about a complicated man…how he worked to save his life and bring his men back home. He failed to keep them safe; poor fools…the god kept them from home. Now…tell the old story for our modern times. (Wilson (2018), 1)

Her rendering of the Greek “ανδρα μοι έννεπε, Μουσα, πολυτροπον…” (Homer, Odyssey line 1 (Murray)) is striking because “πολυτροπον” (literally meaning “many-turned”) describing “ανδρα” (Odysseus) is translated here for the first time as “complicated.” Past translations have opted for “many twists and turns” to refer to the complexities of Odysseus’ geographical journey at the hands of the gods, such as George Musgrave’s “tost to and fro by fate”: a passive interpretation (Tracey (2018)). Others like Fagles and Rieu have considered the “many twists and turns” to convey Odysseus’ character, in the sense that he is ‘manipulating’ the lives of others with the “twists and turns” of his character (Roberts (2020)). This is emphasized in the proceeding lines by how he had a responsibility to protect his men yet “failed to keep them safe”, reducing them to “poor fools” subject to divine will – an internalized portrayal of Odysseus. Wilson’s version of “complicated” encapsulates both of these points of view. While she remains faithful to the vague nature surrounding the word “πολυτροπον”, she prioritizes authenticity to present the “vast complexities of Odysseus in his many disguises” (Wilson (2019a)), and provide greater insight into his multi-faceted character and the elaborate story ahead.

Although the title of the poem suggests Odysseus should be the main focus, Wilson also highlights other characters because they contribute to the narrative, particularly the conflict within his character. While other translations silence their viewpoints, Wilson sympathizes for those he abandons, mutilates, and allows to die (his family, his men, Calypso, Circe, Nausicaa) as he sacrifices their nostos (homecoming) – a central theme of the epic – in order to achieve his own. In this way, she immediately undermines the image of Odysseus as an “unproblematic male western hero” or a “good guy” and instead invites the reader to engage more critically with his “moral ambiguity” (Tracey (2018)).

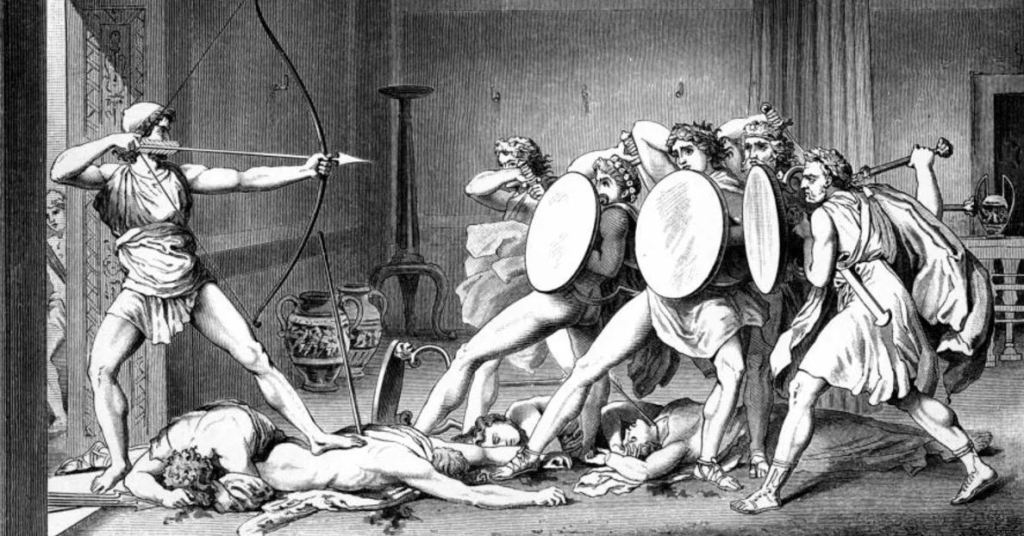

According to Wilson, while “lots of translators only present the narrative in one view,” (Wilson (2019b)) she considers numerous possibilities. She narrows in on the emotions and broader themes, delivering her translation with a particular sensitivity and rawness. Another instance is found in Book 22’s gruesome depiction of the hanging of the slave-women who “slept with” (more likely raped) the suitors. What distinguishes Wilson’s translation in this excerpt is the dignity she injects and sympathy she has for the women. In the Greek, as the women are on the verge of death, they are compared to trapped birds. This expression is rendered in different ways. Richard Fagles likens their situation to “flying in for a cozy nest but a grizzly bed receives them,” (Homer, Odyssey (Fagles, p.378)) where the animalistic lexicon dehumanizes and degrades the women by trivializing their fates.

However, Wilson’s interpretation is arguably more convincing and insightful – the women are like the birds with their “own motivations and perspectives.” (Wilson (2019b)) It is no coincidence that the theme of homecoming recurs, as they fly back to the αυλις (can be a human dwelling), and like Odysseus, they want a nostos. Wilson’s translation “…as doves or thrushes spread their wings to fly home” (Homer, Odyssey (Wilson (2018) 409) reinforces the importance of nostos to demonstrate their desperate plight, thereby evoking pathos for the women who will never have one.

Her intentions and priorities are echoed by translator Josee Kamoun: “It is through the desire to open up new perspectives on the original work and to multiply its ramifications that a retranslation is justified” (Kamoun (2018)). We see how distinct word choices seem immaterial on a microscopic level but hugely impact the overall picture – for instance, the concept of a “good guy/hero” in the Classical World is scrutinized and the perception of who and what is important in the text is broadened. These additional reflections created by the modern translation of a timeless text provide a fresh literary perspective on elements of the poem that have previously been neglected.

New translations of ancient texts furthermore address entrenched misconceptions within literature regarding disenfranchised groups in that society – undeniably applicable to society today. This forces readers to contemplate contemporary ethical questions. Again in the Odyssey, many translators treat the word “slave” in a taboo manner. It could stem from biases surrounding their race, gender or socio-economic status or an aim to glamorise this world, where Odysseus, the quintessential “good-guy”, is not supposed to own slaves. Yet he does, touching on an ‘uncomfortable truth’. While Fagles and Rieu refer to Eurymedusa, a slave of Nausicaa, utilising euphemistic language such as “chambermaiden” and “nurse” and male slaves as “servant” and “swineherd”, Wilson uses “slave” (Roberts (2020)) to honestly portray the world that the literature is set in, where slaves were not free and had no voice. By diverging from past translations, Wilson illuminates the horror of slavery, a “condition of existence” (Rieu (2003) xxvi) and its integration into the hierarchical framework of society. Unfortunately, this resonates with the modern conscience, with the Guardian reporting in 2019 that there are still over 40 million slaves globally (Hodal (2019)).

Unsurprising given the misogyny prevalent in the Classical world, a large number of women were victims of slavery. Unfortunately, some translators insert gendered abuse and incrimination into certain passages, unparalleled in the source language. Returning to the slave-women in Book 22, this scene has previously been depicted using misogynistic slurs:

Fagles p.378: “You sluts – the suitors’ whores!”

Fitzgerald p.569: “I would not give the clean death of a beast to trolls…you sluts”

Lombardo p.548: “the suitor’s sluts”

The source text describes the women as “αι…παρα τε μνηστηριον ιαυον…” (Homer, Odyssey (Murray, lines 464-465), translating literally as “the women…lying besides the suitors”. Despite arguments that it reflects sexist attitudes in the Homeric era, there is nothing in the Greek to suggest they should be portrayed in a derogatory manner. Wilson, making visible the “cracks and fissures in the [poem’s] constructed fantasy” (Wilson (2018)), describes the women more neutrally as “the girls…who laid beside the suitors” (Wilson (2018) 409). She corrects the mistakenly embedded misogyny in previous translations and exposes the culture at that time of women, even as minors, being sexually exploited – again, a frightening reality existing today. She challenges the misguided assumption that women should be viewed and treated as sexual objects, stressing that they too are human. This can be seen in the violent description of their deaths touching on the movement of their feet, which Wilson describes as “twitching for a little while”, pitying the women and (Wilson (2018) 409) emphasizing their vulnerability in the face of the suitors they were forced to sleep with. This contrasts to:

Fagles, p.379: “They kicked up heels”

Fitzgerald p.569: “Their feet danced for a little”

Lombardo p.549: “Their feet fluttered”

These translations dehumanise the women. The first two condemn their sexual behaviour, as they are “dancing” like party-girls driven by desire. The third, through the verb “fluttered”, treats the women as animals. All three strongly justify their fates on account of their sexual behaviour. Again, these pejorative terms have been inserted into the Greek and are more reflective of contemporary sexist attitudes. Re-translating ancient texts compel the readers to reconsider past assumptions embedded in translations and wider implications they hold about society’s standards.

Cicero, writing in the 1st century BC, defines translation as “putting it into a language which conforms to our ways” (Hardwick and Taplin (2010)) In some cases, this is necessary to avoid punishment. For example, the lyric poetry of Sappho, a lesbian poet writing in the 6th century BC, have been translated into Russian. However, under the Soviet regime where homosexuality had harsh consequences, her works were adapted to appear strictly heterosexual through de-eroticising, gender-switching or simply omitting signs of homosexuality (Barker (2020)). On the other hand, translators strive to “foreignize” translations to acknowledge differences between the source and target cultures. For instance, Tony Harrison’s translation of Aeschylus’ Oresteia uses the words such as “he-child” and “she-child” (instead of “son” and “daughter”) and “bed-bond” and “blood-bond” (“marriage” and “blood-relationship”) to express that the play is not about his culture (Harrison (1981). However, the acts of “foreignising” and “domesticating” do not have to be mutually exclusive.

Wilson includes some details considered to be “foreignising”, like the goddess Demeter having cornrows in her hair (Gabrielson (2018) 115). This challenges the societal assumption that all gods/goddesses are white. At the same time, she remains faithful to the oral tradition of Homer by setting her translation in iambic pentameter, the closest equivalent in the Anglophone tradition to dactylic hexameter, the original metre of the Odyssey. Hence, retranslating these ancient texts are meaningful as they allow translators to explore, understand and identify the impact of ‘foreignising’ and domesticating characters and subjects, and how they reflect cultural norms.

In a slightly different vein, new translations of ancient texts have the power to revitalize texts in innovative ways. Oliver Taplin from Oxford University points out that translation is often considered an art that is exclusively literary (Hardwick and Taplin (2010)). However, he suggests that translation can assume a variety of forms and contexts. This is supported by Margherita Laera who deconstructs what it means “to translate.” She argues that translation is something that is always changing, subject to culture and society, so it can therefore be coined as an adaptation (Laera (2019) 25-26). Translations as “adaptations” are capable of facilitating conversation on important social issues. This is demonstrated by Euripides’ tragedy Medea, which has been “translated” into multiple forms/contexts since it was first performed in 431 BC. In Guy Butler’s South African version of Medea performed in 1990, Medea and Jason are in a mixed-race marriage and the race of the children is unclear, raising deeper questions about whether colour matters (Griffiths (2006) 112), especially relevant under Apartheid. In contrast to this political and racial commentary, Brendan Kennelly’s “translation” is centred around his personal experience in a psychiatric institution and how he contextualizes Medea in a similar situation, driven to the point of anger and insanity by an abusive relationship (Griffiths (2006) 113). The impact of retranslating ancient texts in new contexts and forms is significant and in both cases here allow the audience to engage with contemporary emotional, political and social issues in a more creative and impactful way.

Finally, new translations can be agents of inclusion, making texts accessible to all. Composer Julian Anderson, through his 2014 operatic version of Sophocles’ Theban plays, expresses the characters and underlying themes through music. For example, in Antigone, Anderson represents Creon’s drive for power by notating the orchestral score with individual beats and the Chorus repeatedly singing “Your Word Is Law”. In a 2018 interview, he reveals how on the page, this scene looked like “bars of a prison” (Nicholls (2018) 26-27), intended to create an atmosphere of oppression and bring out the dictatorial side of his character. By staging the Thebans in this way, this “translation” of form would appeal to those who learn through visual stimuli and engage with texts through analysing the music, as opposed to reading, the most popular medium through which to access ancient texts. Similarly, retranslating attracts a larger audience who engage with these timeless texts in different ways.

The need for new translations of ancient texts is clear and arguably its importance is increasing. New translations provide a fresh lens with which to examine a work, discover new elements and explore more comprehensive perspectives. At the same they can eradicate bias in past renderings, and invite readers to consider the impact of domesticating and foreignizing a text to either reflect or reject the values of a text within the context of a specific culture. Finally, retranslations explore deeper contemporary political and social issues and include the broader population in these dialogues. Ultimately, Classical texts more often than not deal with the human condition, from the most noble acts to the most depraved, which is relevant across cultures and time.

Ines Choi

Bibliography

Barker, G. ‘Classics and Queerness: Translating Sappho straight into Russian’, University College of London (2020) [lecture]

Dryden, J. Ovid’s Epistles: With His Armours. London (1776)

Fagles, R. Homer’s The Odyssey. London (2006)

Fitzgerald, R. Homer’s The Odyssey. New York (1961)

Gabrielson, M. ‘Homer, Emily Wilson, trans. The Odyssey’, New England Classical Journal (2018)

Griffiths, E. Medea. London and New York (2006)

Harrison, T. The Oresteia: A trilogy by Aeschylus. London (1981)

Murray, A.T. Homer, The Odyssey. London (1919)

Kamoun, J. Orwell’s 1984. Paris (2018)

Laera, M. Theatre & Translation. London (2019)

Lombardo, S. Homer’s The Odyssey. Cambridge (2000)

Hardwick, L. and Taplin, O. ‘What is Translation?’, University of Oxford Podcasts (2010)

Nicholls, M. ‘Staging Thebans with Julian Anderson’, Omnibus 76 (2018)

Rieu, E. Homer’s The Odyssey. London (2003)

Roberts, D. ‘Emily Wilson, trans. Homer: The Odyssey,’ Spenser Review 50.1.3 (2020)

Tracey, J. ‘The Complicated Radicalism of Emily Wilson’s The Odyssey’, Ploughshares at Emerson College (2018) https://blog.pshares.org/the-complicated-radicalism-of-emily-wilsons-the-odyssey/

Wilson, E. Homer’s The Odyssey, London (2018)

Wilson, E. Sebald Lecture, British Centre for Literary Translation (2019a)

Wilson, E. Sixth Annual Adam and Anne Amory Parry Lecture, Yale University (2019b)